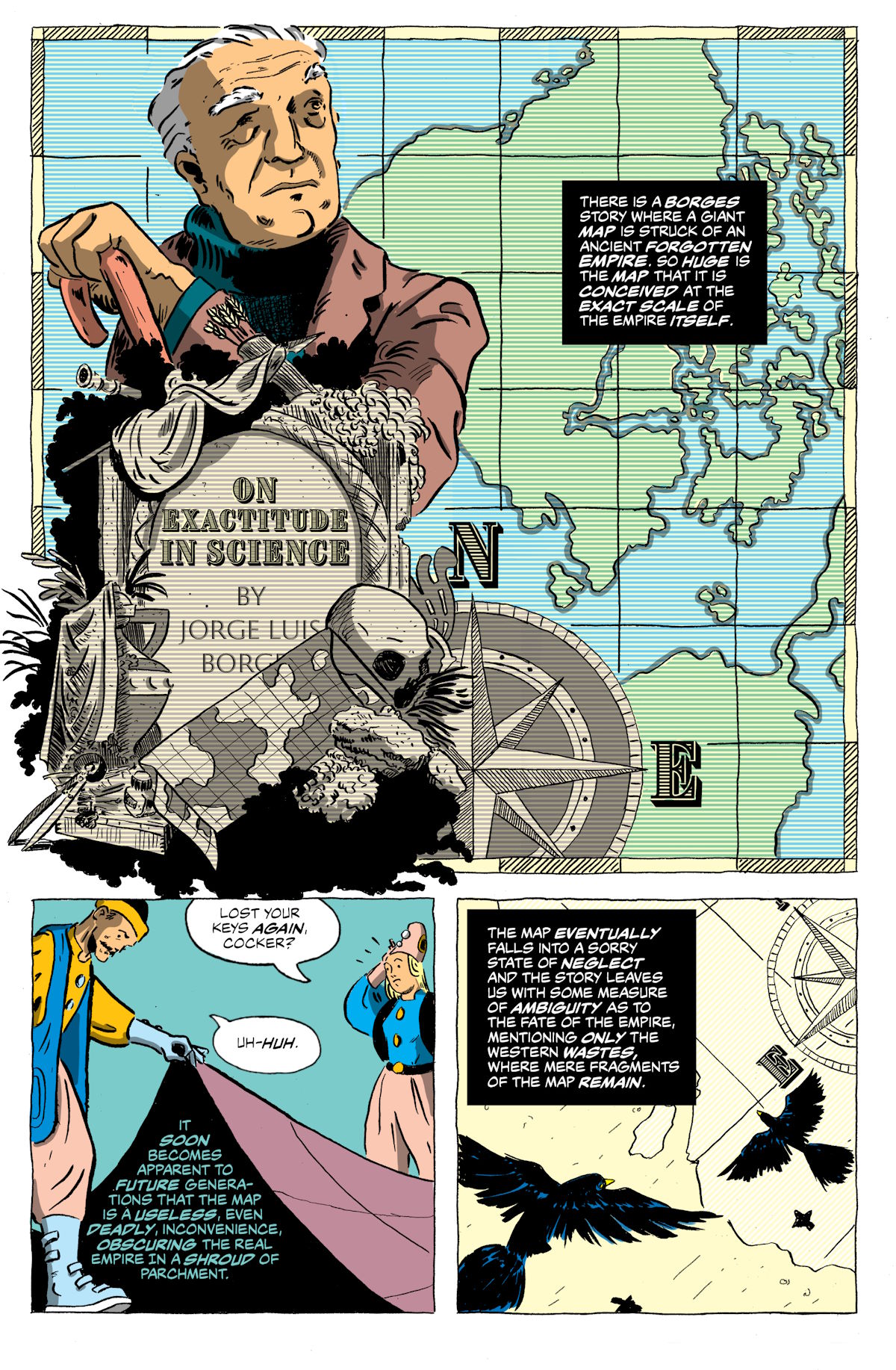

Impossible maps and models shape grand narratives about how the world works, how people relate to each other and nature.

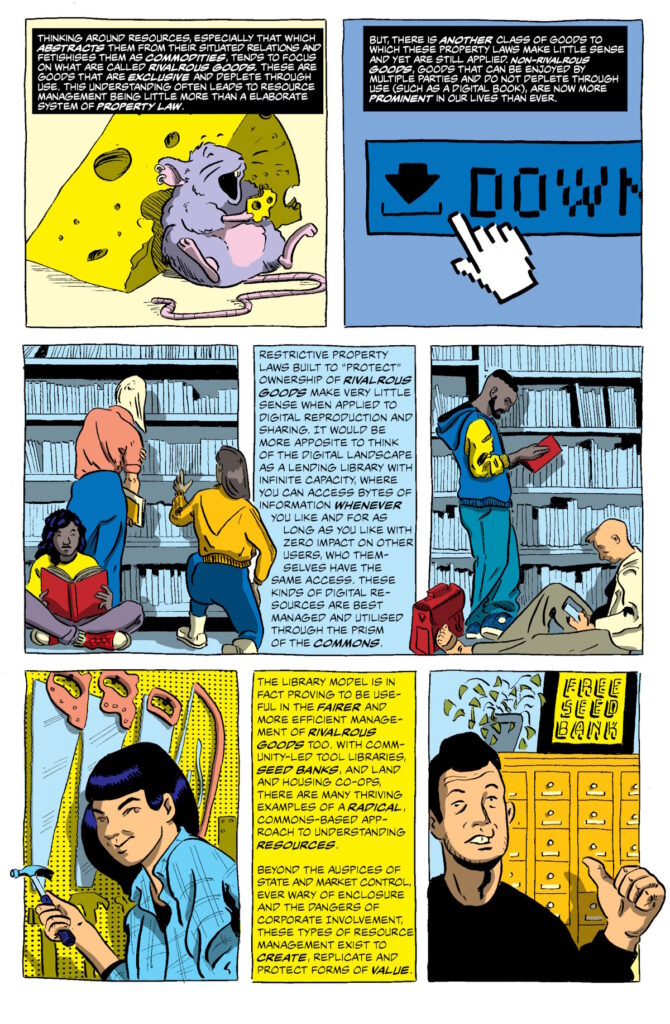

In the second comic from Future Natures, created by Tim Zocco with Amber Huff, we explore maps, models and abstraction that can warp how we perceive and understand space, human nature, power and crisis and shape contestations over knowledge and struggles against enclosure. These struggles don’t just involve things like land and resource grabs, but also, relations of value and care, people’s autonomy and even imaginaries of better worlds and possible futures.

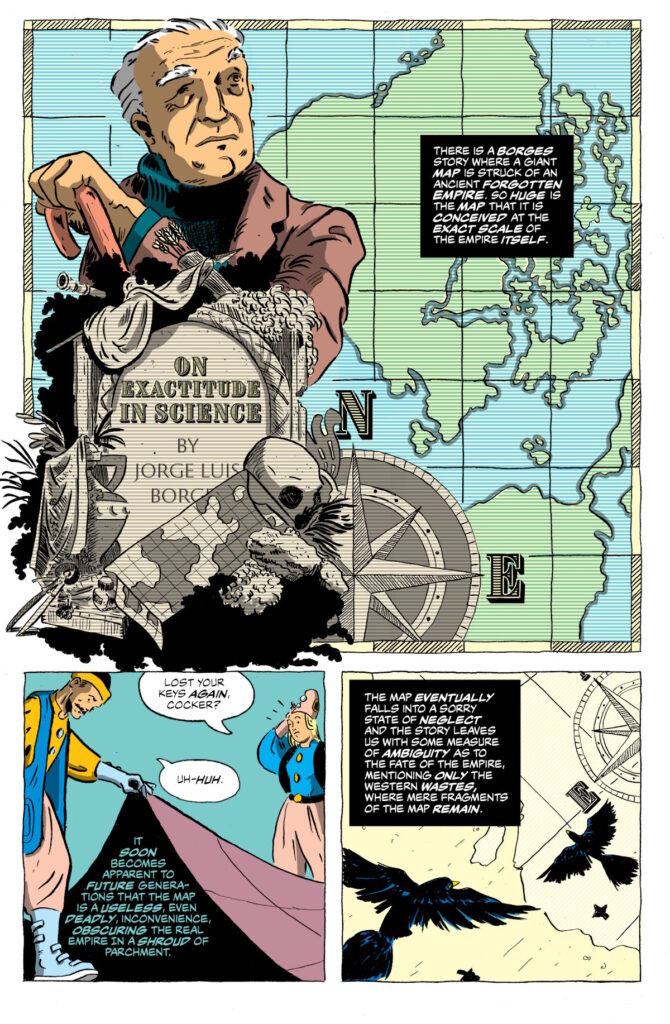

Maps tell stories about relationships. They can tell us how to get from here to there (relationships between places), explain a theory or concept (relationships between ideas), show cause and effect, or show changes and flows over time and space.

Because of this, maps can be an important tool to help us to see and understand the relationships between things in different ways.

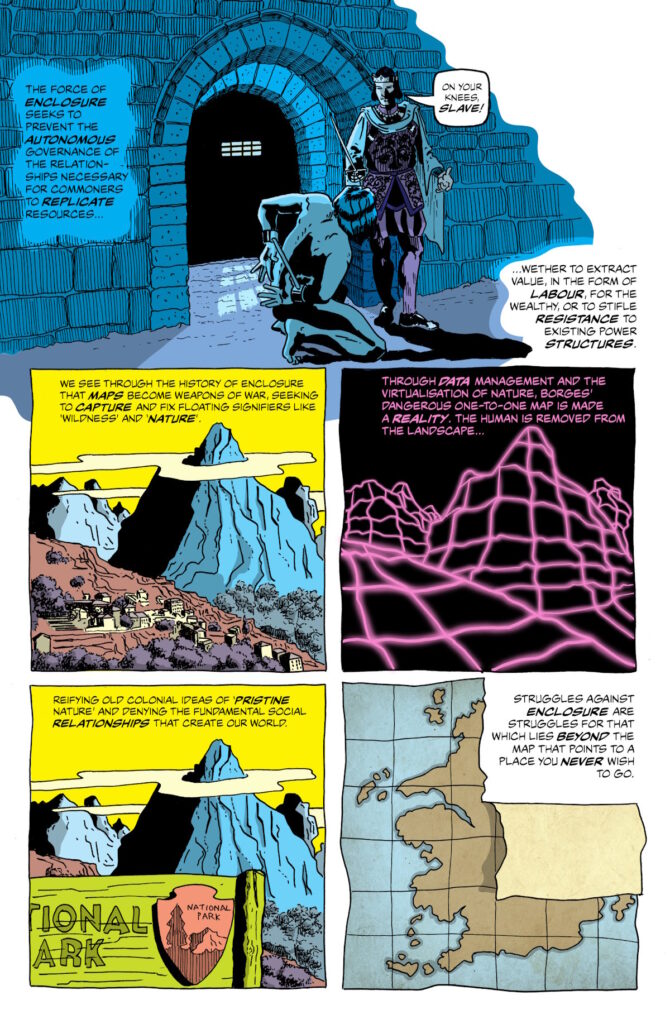

We generally trust maps to represent something in the ‘real world’. But maps aren’t just objective tools. Maps use abstraction and representation to tell stories about the world and these stories are always embedded with power relations. Maps can direct what we see and don’t see in it and how we should move and behave in it. Like a narrative in a book, visual representations in maps can filter how we see and understand relationships between ourselves and places, peoples, things, and ideas.

In the best stories, the storyteller’s act of world-building allows a reader to slip effortlessly between the logics of our daily lives and those of another universe that the storyteller constructs. We often talk about getting ‘lost in a book’. It just so happens that the more power a class of people possess, the more their interests, imaginaries and values tend to find their way into the stories that get told through the maps that get made.

With maps, world building can slip into world-making – the map can become an instrument of politics, embodying the ideological assumptions and power relations that underly its production, projecting these back to the observer, and causing us to confuse the projection for what it is meant to represent. Like wearing a VR headset, the stories told by maps can create slippages between the relationships imagined or projected in the mapmaking and our concrete reality and experience.

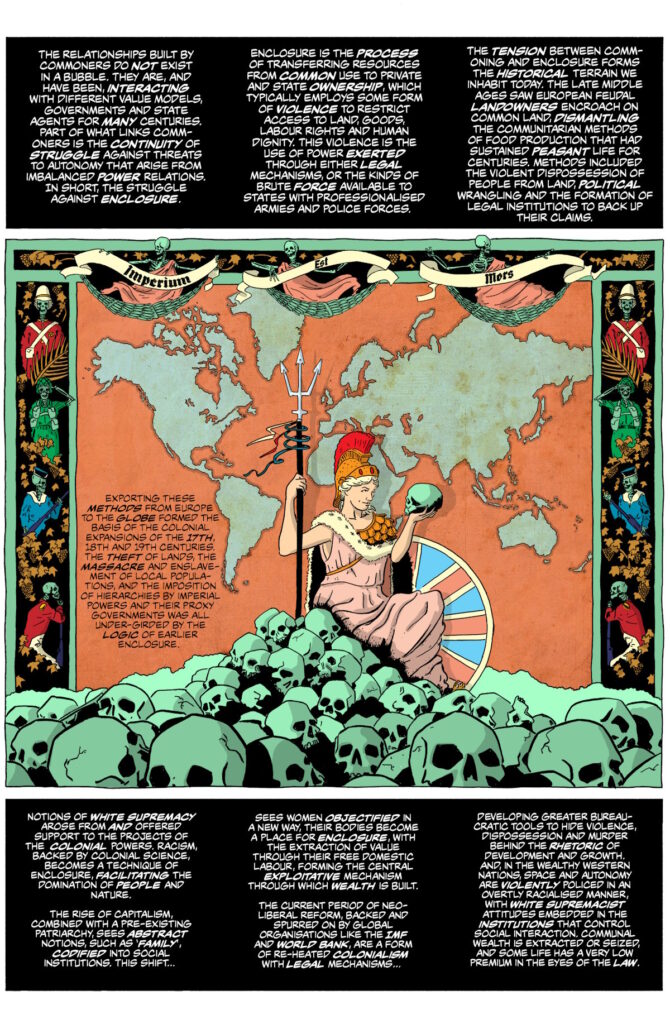

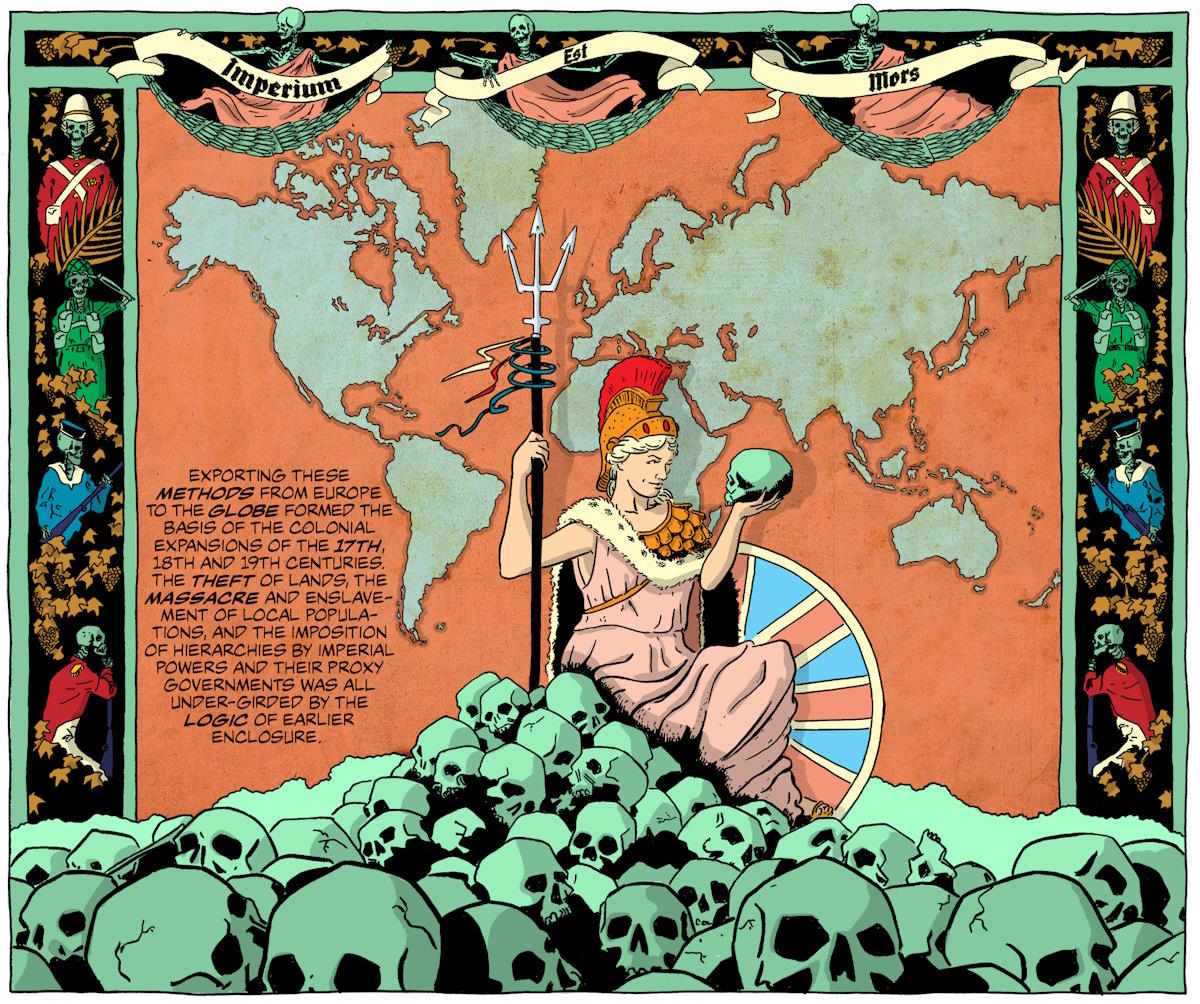

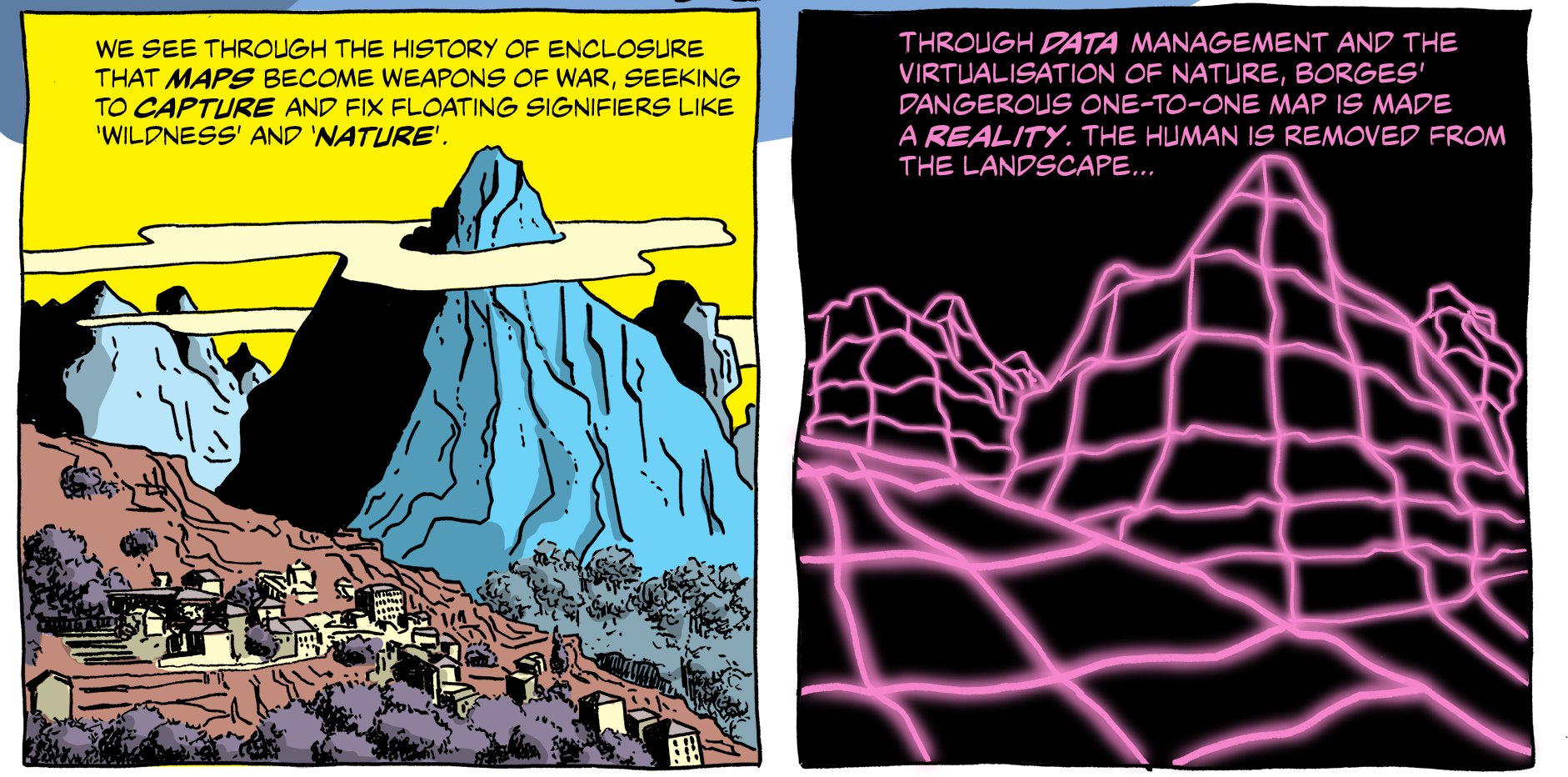

Mapping, understood critically, is a type of technology that has been used in projects seeking to dominate people and nature. This has been done by states wishing to assert territorial sovereignty and by empires wishing to represent the world in such a way as to claim dominion over vast territories, expand means of bureaucratic and economic control, and enclose commons. It has been used to represent space and landscape as ‘empty’, ‘degraded’ or ‘unproductive’ to justify enclosure for top-down conservation, and by corporations looking to secure large-scale agricultural investments extractive reservoirs of cheap labour and cheap nature.

But this politics can also work in our day to day lives; it can work used subtly, and slippages between the map’s representation and the lived space can warp our perceptions of space and time, direct our movement and control our behaviour, and filter what we see as ‘choices’ and what we can imagine as possibilities without us even realising.

Just like maps tell stories, stories of all sorts can also work like maps, making some pathways and voices visible while obscuring or supressing others. When stories get told and re-told, particularly those backed by scientific and political authority, the pathways and voices that are privileged and represented can shape the way we see and understand and act in the world, our values and relationships with other people and with our environments, our ideas about whose claims carry weight. Familiar ‘tropes’ become received wisdoms, so ingrained that we might not think to question where they come from or whose interests they support.

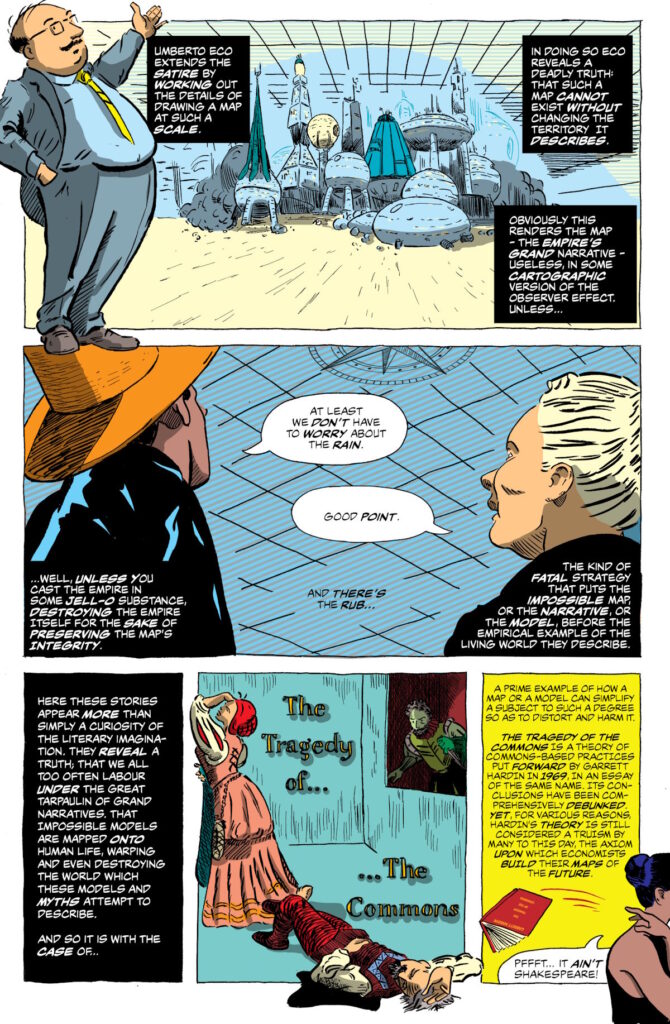

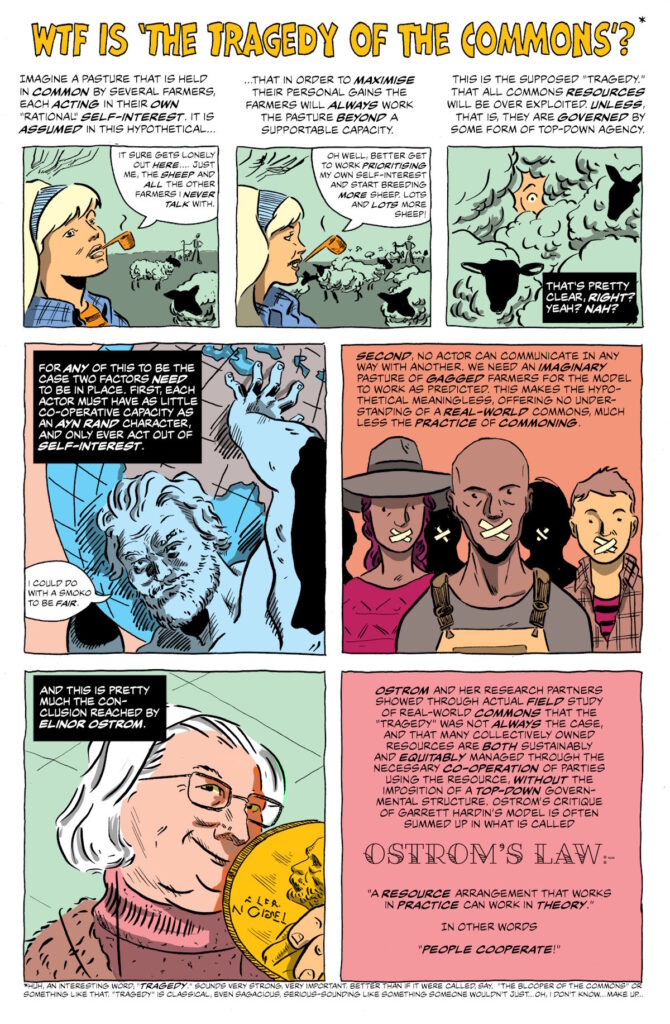

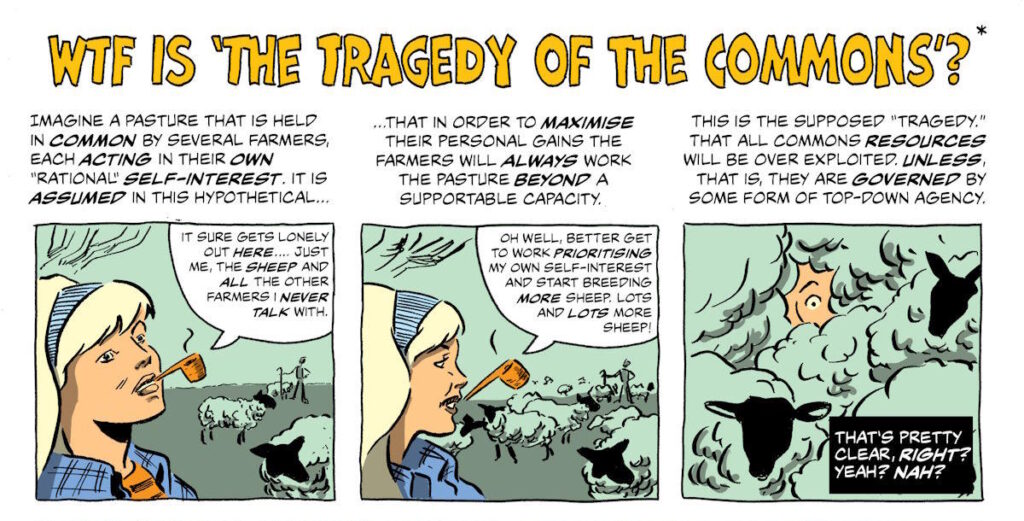

The ‘Tragedy’ of the Commons

For example, Garrett Hardin’s proposed ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ presents a model – in the form of a story – that reinforces the idea that state or private control of land and nature is necessary to avoid inevitable localised ‘tragedies’ of land and natural resource degradation caused by the assumed self-interest and over-exploitation by everyday people making use of resources.

This story repackages old tropes about human nature, morality, self-interest and scarcity that have been used to justify all manner of abuses and violence – authoritarianism, colonisation, territorial exclusion, cultural erasure and ethnic cleansing, eugenics and racist immigration and population control policies. But it omits and invisibilises the basic facts that humans are social beings and of the ‘existing commons’, that people all over the world (and throughout history) communicate, cooperate and use situated knowledge and self-governing institutions to sustain and maintain their environments outside of direct state and market control.

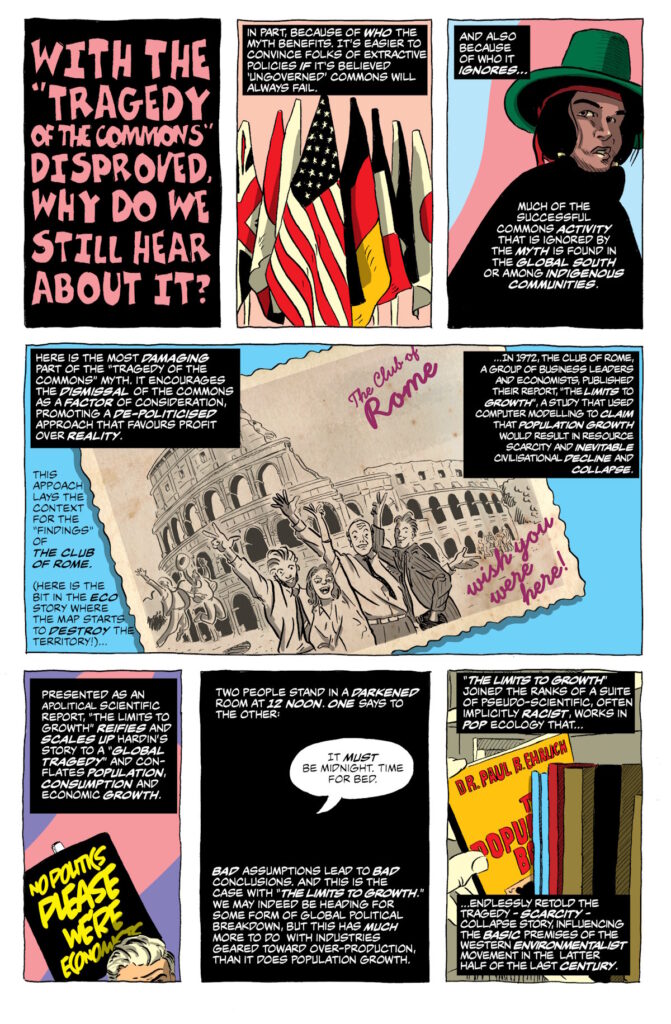

Despite being widely discredited by social research, the ‘tragedy’ story has become received wisdom in public and policy discourse. It provides a simple model that maps a problem, its causes, its consequences and its ostensible solutions. In scientific literature and pop ecology, the story time and time again is used to frame understandings of the causes of environmental degradation and people’s capacities for self-governance, particularly in the Global South. It continues to inform policy narratives about environmental change, conservation and development that justify enclosure, dispossession of people who directly use the land, and the widespread privatisation and commodification of land and nature.

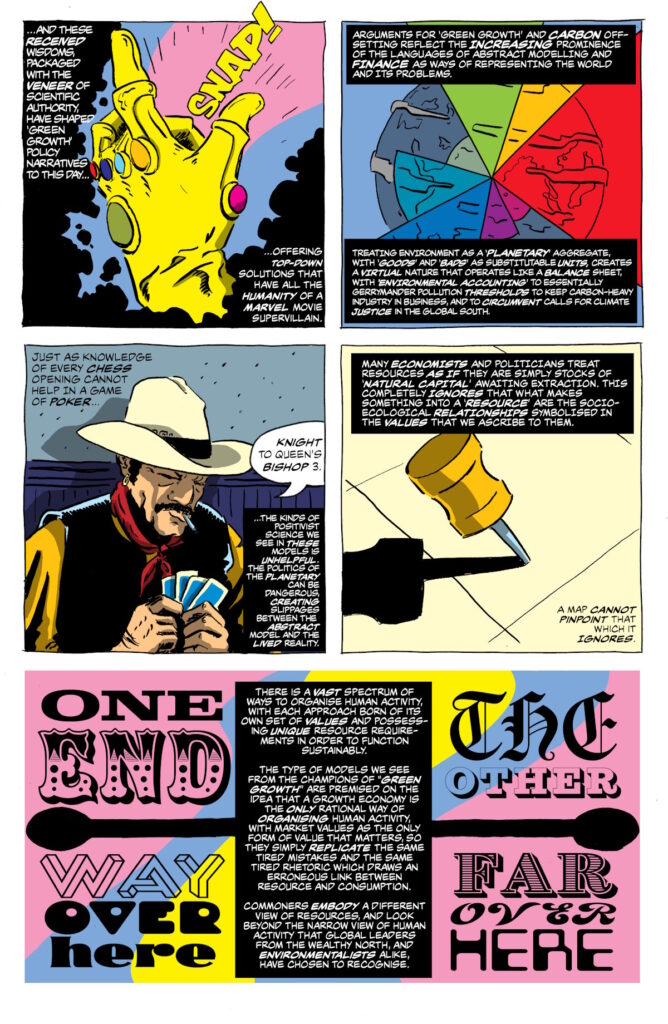

Since the 1970s, global-scale models and discourses tell stories that explicitly or implicitly link population growth with increasing scarcity, environmental thresholds or collapse. These stories use abstraction to show a planetary system on the brink, spoiled by the over-indulgence of an undifferentiated and growing mass of ‘humanity’ that has collectively caused global crises of anthropogenic climate change, biodiversity loss and landscape degradation.

By representing the abstract and aggregate ‘planetary’ as the unit of concern, global inequalities and histories of struggle against exploitation and violence are erased, social differences are flattened and vast imbalances in economic and political power are smoothed. We can no longer see the places and landscapes, nor relations and processes through which globalisation, wealth accumulation and cascading ecological problems have been mutually constructed.

Seeing beyond the map

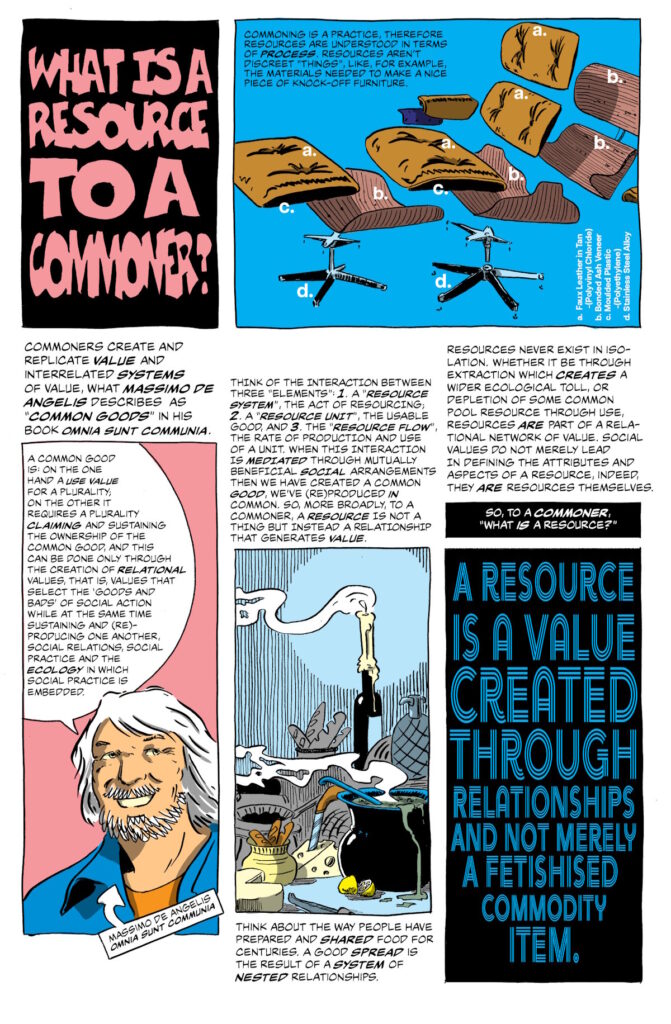

Big stories of planetary crisis scale-up the old ‘tragedy’ story, creating slippages between the world we can see, touch and experience, and a hyperreal pixelated virtual nature rendered as data points that can be parsed, priced, substituted, exchanged to generate new forms of value to fuel continued growth.

All of nature becomes a ‘global commons’: not an actual commons made up of people and their situated social and ecological relationships, uses and values – but, as in Hardin’s line of thinking, as a stock of resources in the economic sense. A stock that’s in urgent need of being secured, enclosed, brought into the market gaze, to enable technical management and financial rationalisation, and to ostensibly save us from ourselves.

But these politics are always incomplete, and seeing them helps us see beyond ‘the map’. Looking beyond grand narratives and just-so stories, to struggles against enclosure and erasure in different places and times, we can find or imagine new relationships, new forms of value and new ways of getting along. Each struggle offers a portal through which to glimpse another way to live, another set of possibilities, another world.

Read the comic

Read the comic below, or download it as a PDF. For a high-resolution version that can be printed, email us: [email protected]