by Jo Walton, University of Sussex

Climate change is drawing us into a complex and uncertain future. Climate Uncertainty and the Arts is a working paper which explores how the arts might contribute.

One thing is certain: the risk management techniques we currently use to control companies, projects, and financial portfolios are dangerously overrated. Within carefully defined limits, they are perfectly okay at what they do. But climate change demands big societal changes, and for those changes we shouldn’t rely solely on such techniques — everything from enterprise-level risk matrices, to Climate VaR or portfolio temperature alignment — any more than we should try to cross the Pacific Ocean in a toy boat.

Unpredictability and uncontrollability are at the heart of climate change. The most promising approaches to climate action — things like mission-driven approaches at the enterprise level, transformative climate justice at the policy level — all share this insight. When we dwell with the unpredictable and the uncontrollable, instead of wishing it away with sophisticated calculations, this tends to reinforce the importance of participatory approaches.

That is, the more you realise you can’t confidently know the best course of action, the more important it is to empower the voices of all those who may be affected.

All this implies a fundamental cultural shift in how we think about the future. This raises the question of whether creative practice might help us to relinquish our counterproductive certitudes, and to develop new ways of communicating and collaborating.

So how might literature, theatre, music, games, digital culture, and other forms of creative practice contribute in a time of climate crisis?

Climate Uncertainty and the Arts explores these themes. If you are bringing creative practitioners into a project, it is tempting to think of them as experts in communication, and/or stirring emotions in the human heart. But Climate Uncertainty and the Arts proposes that this may not be an ideal framing. True, artists sometimes do these things, but sometimes they don’t! To avoid disappointment, perhaps we should focus on what creative practice can more reliably accomplish.

For example, participatory arts projects can feed into other participatory processes such as stakeholder engagement and co-creation. Arts spaces can often help participants to wriggle free of habits of thought and feeling, however temporarily, and encounter issues in a new light. Bringing creative practitioners into a project can also diversify the perspectives and lived experience which inform it. Sometimes, that might mean turning certainty into uncertainty.

Of course, to really get an idea of what the arts can and can’t do, concrete examples are invaluable.

The fantastic CreaTures project, for instance, includes a portfolio of twenty artistic experiments, as well as a comprehensive framework for commissioning, designing, and evaluating transformative arts practices. The Treaty of Finsbury Park, just one experiment featured in the CreaTures catalogue, is an immersive fiction that explores Live Action Role-Playing as a way of building empathy with the non-human.

Climate Change Theatre Action is a worldwide festival of short plays about the climate crisis, explicitly linked to bringing communities together for action (this year’s theme is ‘All Good Things Must Begin’, an Octavia Butler quotation). The Artists and Climate Change blog is filled with interviews and features on climate-related art. Radical Ocean Futures uses Science Fiction Prototyping to explore the future governance of the high seas, while The UK Earth Law Project is reimagining legal judgments from ecocritical perspectives.

Climate Visuals is an extensive collection of photography, much of it under an open licence, whose collection and curation is inspired by scientific research into climate communication. PASTRES’s own Seeing Pastoralism exhibition explores how pastoralists around the world understand, experience and respond to uncertainty through images recorded by researchers, photographers, and pastoralists. The Future Natures initiative is exploring commoning and enclosure through narratives and art, including zines and comics. Playful methods are used in climate education workshops such as Climate Fresk and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center’s Climate Games collection.

That’s just a few!

In my own work in this area, I am of two minds. Whenever I think about arts practice in the abstract, I want to emphasise drawbacks, the limitations, the potential pitfalls. Art has a bewitching aura about it, and as climate crisis intensifies, it becomes tempting to ask impossible things of art. The working paper Climate Uncertainty and the Arts contains a strong dose of such scepticism. Problems framed within the cultural sphere — as though they could be solvable just with more inspiring and innovative creative practice — are often really problems of political economy, rooted in unequal distributions of power and resources.

Earlier this year, a special issue of the journal Vector, co-guest-edited by science fiction writer Stephen Oram, explored ‘applied science fiction’ in all its many manifestations. In our editorial for the issue, Polina Levontin and I again sounded several notes of caution — sufficient for a short caution melody. For example, even the philosophy of openness and experimentation, so pervasive within creative arts practice, has its limits:

“[…] when was the last time you heard a writer or other creative practitioner extol rigidity over flexibility, or doing something perfectly on the first go over iteration and adaptability? […] Yet we also all know social transformation sometimes does require things to be rigid and steely. Sometimes it does require a thing to be done perfectly on the first go, during some narrow window of opportunity.”

On the other hand, when you are actually engaged in creative practice, these sorts of doubts seldom get in the way. You hope that they don’t evaporate entirely, and that at some level they are informing your creative practice. But the truth is you are mostly not thinking about these things that much. You are thinking about what you’re making. The thing that doesn’t yet exist has its own elusive logic, and that draws in most of your attention and energy.

How different is this, really, to being absorbed in the intricacies of some risk management tool? — I’m not sure. Either way, that’s what it’s like: your time is spent trying to tune into that pattern of translucent possibilities, trying to making them more and more tangible, more and more real.

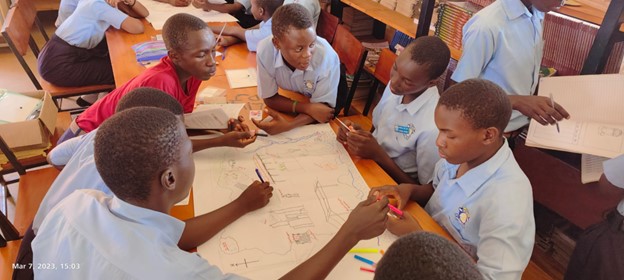

Kampala Yénkya is a storytelling and mapmaking game, which I helped to develop in 2022-2023 in collaboration with Dilman Dila, Maurice Ssebisubi, Polina Levontin, Jana Kleineberg and others, supported by the Sussex Sustainability Research Programme. What I like about Kampala Yénkya is that it is creative practice that is generative of more creative practice. It is a game which combines an educational climate quiz, collaborative storytelling, and drawing / mapmaking, to help imagine what Kampala might look like in the year 2060. Maurice led the playtesting at Ngogwe Baskerville Secondary, Victoria Ssi Secondary, Sacred Heart Secondary, and Nyenga Secondary; an adapted version was also playtested with University of Sussex students.

As I write, twenty copies of the game are being distributed around schools in Uganda, and another twenty will be on their way shortly; there is also a version of the game that can be played with ordinary playing cards, and a Luganda version in the works. Follow-on support from PASTRES has helped us to continue work around the game.

We launched a website in July, and are currently playtesting an activity book, which will also contain the original science fiction written by Dilman as inspiration for the game. We will also be reflecting in greater detail on the process of creating the game in the third edition of Communicating Climate Risk, scheduled for late 2023 or early 2024.

We are interested in developing localisations of the game (or who knows, maybe completely different games), and would love to hear from potential collaborators around the world ([email protected]).

Read the working paper

Walton, Jo Lindsay (2023) Climate Uncertainty and the Arts (1.2). Sussex Humanities Lab

Funding note

The PASTRES programme (Pastoralism, Uncertainty, Resilience: Global Lessons from the Margins) is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) (Grant No. 70432), and co-hosted by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the European University Institute (EUI). We gratefully acknowledge the support of a PASTRES small grant in producing Climate Uncertainty and the Arts, Vector: Futures, the Kampala Yénkya website, and Communicating Climate Risk: 3rd Edition (forthcoming).

The original Kampala Yénkya game was funded by the Sussex Sustainability Research Programme, with some additional support from the Sussex Digital Humanities Lab and HEIF (Democratising Digital Decarbonisation).