In this comic, Tim Zocco reflects on a strange encounter with mining and conservation in Madagascar, leading to a glimpse into a horrifying chapter in the country’s colonial history.

In this short introduction, Tim Zocco explains the background to the comic.

The most successful liars are the ones who have convinced themselves.

Through a twist of fate, I found myself in Madagascar at the start of the year, attending a garden party in a gated community on the edge of the capital city, Antananarivo. Despite everyone’s predictions of heavy afternoon rainstorms, the weather was bright and humid. As I took shade under a leafy tree covered in cobwebs and the biggest spiders I have ever seen, I was introduced to a conservationist.

Within seconds, he was pulling coloured charts and tables of statistics from a stack of laminated cards fastened by a strained tangle of elastic bands. I was told about deforestation levels, shown heat maps, and presented with forecasts and projections for regions of an unfamiliar country.

It struck me as comical, the way he went through this entire presentation with a practiced automation. Was the purpose of all this to leave me bamboozled? In truth, I was completely lost, but almost immediately I did recognise that I was being sold something. There is a rule in network-marketing, those pyramid schemes with names like BetaLyfe™ or EzyHealth®, where any stranger within three meters does not leave without hearing the pitch. I couldn’t help but think this was all some kind of grift.

The real threat, we are meant to believe, is posed by local herders and subsistence farmers who ‘mismanage’ nearby forests. Surely not, I asked, that’s absurd?

It wasn’t until later that evening that a colleague explained the situation over a cold beer. The ‘conservationist’, I was informed, did not actually work for one of the big international environmental NGOs headquartered in the capital as I had assumed. Rather, he worked for a foreign mining company and his job was to promote the narrative that the company’s mining activities are ecologically ‘sustainable’. Apparently, the clear-cutting of forests, stripping of topsoil, use of industrial diggers and dredges to churn up rock, dust, radioactive particles, and all manner of other shit from the earth, not to mention air, water and soil pollutants from the vehicles, transport infrastructure, and other machinery the mine required, did not contribute to substantial ecological degradation or loss of biodiversity.

The real threat, we are meant to believe, is posed by local herders and subsistence farmers who ‘mismanage’ nearby forests. Surely not, I asked, that’s absurd? Yep, was the reply, this is actually a very common ‘story’ about environmental change and ‘development’ in Madagascar, particularly when someone wants access to land that is already being used by rural Malagasy people.

The truth is, I don’t come from the world of international development or public relations, and I’m new to the politics of mining and conservation, so this was all news to me. I think it would be surprising to most people – that what looks like a ‘conservationist’ works for a huge corporation and their work involves shifting the blame for ecological degradation from a rich mining company onto some of the materially poorest and least resourced people on earth. It’s counter to everything that most of us understand when we hear the words conservation, biodiversity or sustainability.

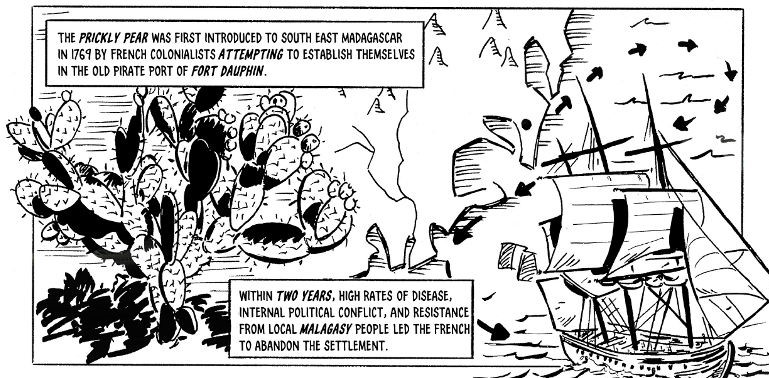

To help me make sense of all of this, my colleague recommended some books and articles to read about the natural history of Madagascar, and more broadly about the roots of contemporary ‘conservation’ in European colonisation and the dispossession and genocide of poor and indigenous folk globally. Late that evening, my colleague told me the story that I present in the following comic. It represents one historical example that explores these facts, that shows conservation as a function of the colonial apparatus, as a lie that those in power tell and of which they themselves seem to have become convinced.

This post was originally published on the ESRC STEPS Centre website.