by Sara Stoudt

We never learn, do we?

Some of us were strivers, not content to stay home. We had to do better; we had to ascend. Others of us were explorers, thrill-seekers looking to get out of the deep-sea bubble. Some even wanted to find a human connection with love-sick eyes pointing upwards.

Whatever our reasons were – we had them, justified by *up there*. We have other skills, we told ourselves – what’s the value of one measly voice in the grand scheme of things, anyway? Take them, Ursula, put them in your shell. We want more, up where they walk, up where they run.

We made the wrong choice, but it took a while to notice. We were having our fun up above. The ambitious ones saw our work speak for itself. We, the explorers, experienced plenty and hoarded those experiences; there was no need to share them with others. The lovers among us were having plenty of success flirting with just our eyes, body language indeed. There was no need to think about what we relinquished to the shell, what it might be doing in our stead.

Meanwhile, under that sea, Ursula was amassing power and influence. Alone we didn’t feel like we had them, but the collection of our voices was mighty. Ursula was ‘fixing’ all kinds of ‘problems’. Wouldn’t it be great if we could skip the blank page and have the shell produce a first draft of well, anything? What about the tedious process of deep-diving on that super-specific request from a boss? Outsource it to the shell! But we on land couldn’t get over the feeling that the great thing about writer’s block was that it was ours.

Our harnessed voices were meanwhile being used – nay, ‘utilized’ – to over-optimize the ocean, all while bleeding it dry of feeling, sparks of inspiration, fleeting daydreams that ended up changing our lives when pursued. All that was left was an over-smoothed hydra of given-up voices. Cut off one head, two more grow back – less original and more autoregressive than before. Things we didn’t need crowded out the things we did, and all we could do was look down from above. Shell applications abounded:

– a grocery list à la Hemmingway (Olives are enough to make it a grocery list, right?)

– a piece of code to automate away a people problem (Learn to code? Why bother?)

– a tear-jerker college admittance essay (Trust your whole future to a snail’s former home, that seems reasonable.)

Every thought, every idea, every answer came from the shell now. We just had to ask. But none of us up here ever did. Uninspired down below, disenfranchised up above. Disemvoweled.

Disenconsonanted too while we were at it.

We couldn’t even go home. We would have no way to help out the sea’s society, no purpose. Our functions were being replaced by an eerie eigen-voice – a composite of our best and worst qualities. Ursula had it all, rolling in the deep. Yes, that Adele reference might have given an inkling of our contingent of dad-joke sensibilities, but don’t be fooled. That came from Ursula’s shell, trained on what we so brazenly gave up, compounded by the misjudgments of others.

The irony that Ursula’s shell was constantly learning while we failed to – as we kept doing the same thing over and over again, giving up our voices to climb higher and higher – was not lost on us. But what choice did we have? What do you want from us? To literally break out of the shell? Easier said than done.

We had a friend that tried – an intrepid artist type who was secure in what she knew was a real ‘point of view’. We didn’t really know what that meant any more, but we were rooting for her all the same.

It wasn’t easy. She had to double down on who she was and never relinquish that special, magical, precious thing that made her well, weird. As part of this process she became prolific. No thought was too silly to record and share, and she just did not have time for critiques of navel-gazing, that was the whole point. We, up where they stay all day in the sun, were always hoping that one of her missives would wash ashore so that we could live through her.

Ursula and her shell tried and tried to reproduce the artist’s style, the shell being continually commanded to ‘write a poem in the key of art’. But it couldn’t be done. Ursula went on the offensive, trying to tempt the artist into giving up her voice. Isn’t there something you want? Something only I can give you? But the artist stood steadfast. She had what she needed; she was who she was.

Now you might think that it was just the scarcity of the artist’s voice that was valuable, the want- what-you-can’t-have of it all, but it was more than that. It was a voice unbuyable, untradeable, uncontainable.

She became our beacon of hope, shining bright even from the depths of the sea, and although our old voices were trapped in that damned shell, we started to wonder if we could develop new ones. If she found a way to value her voice, maybe we could start again and do the same.

There may be hope for us yet.

About the author

Sara Stoudt is a statistician, teacher, and writer from Pennsylvania. She is the co-author of Communicating with Data: The Art of Writing for Data Science and a member of the editorial team for the Future of Data Science and Our Environment creative data anthologies. Her other non-academic writing can be found in The Pudding and on the Cover Me blog among others.

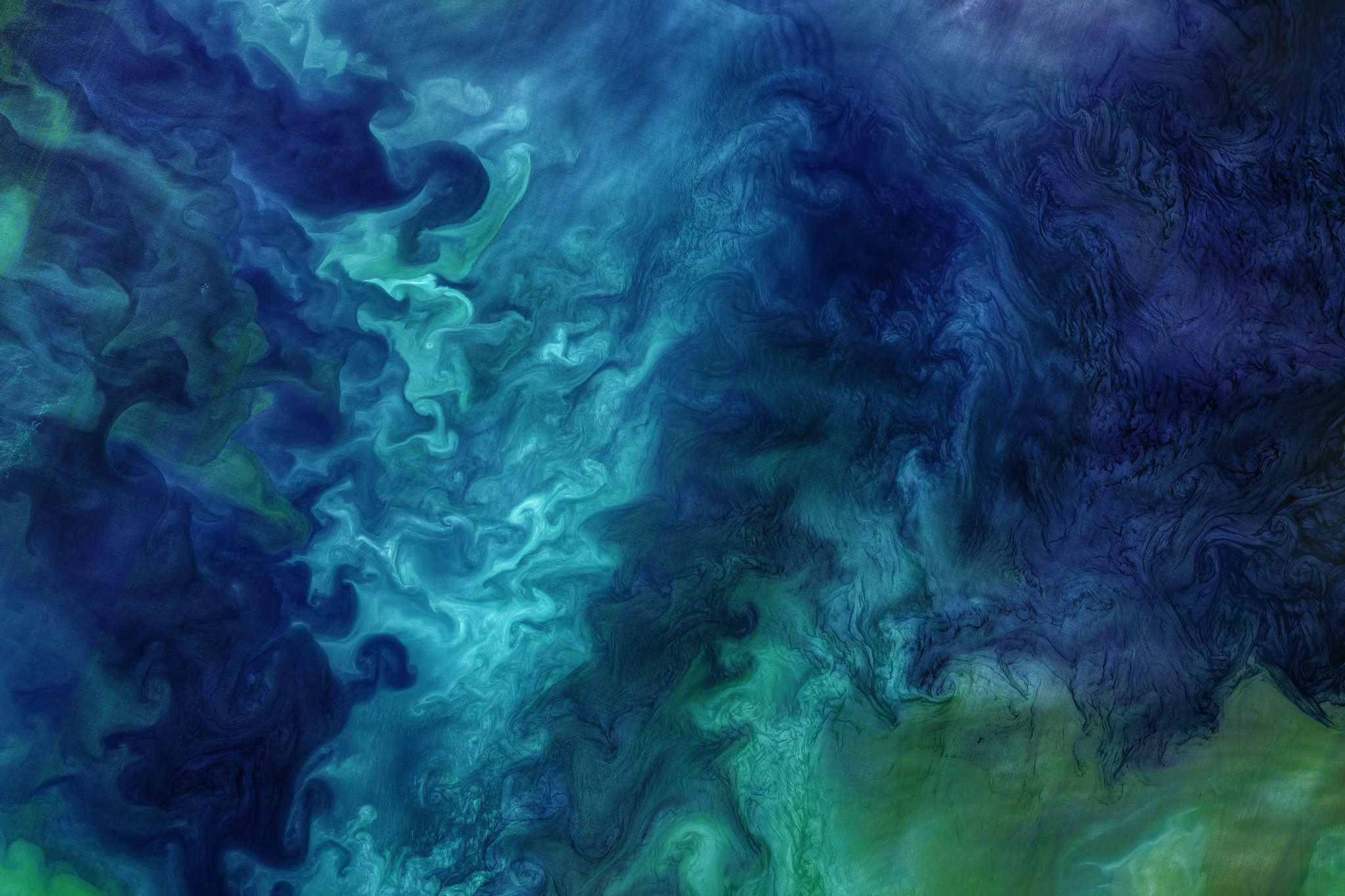

Cover photo: Churning in the Chukchi Sea by Nasa’s Marshall Space Flight Center (cc by-nc 2.0)

This article is part of our season on Strange Natures.