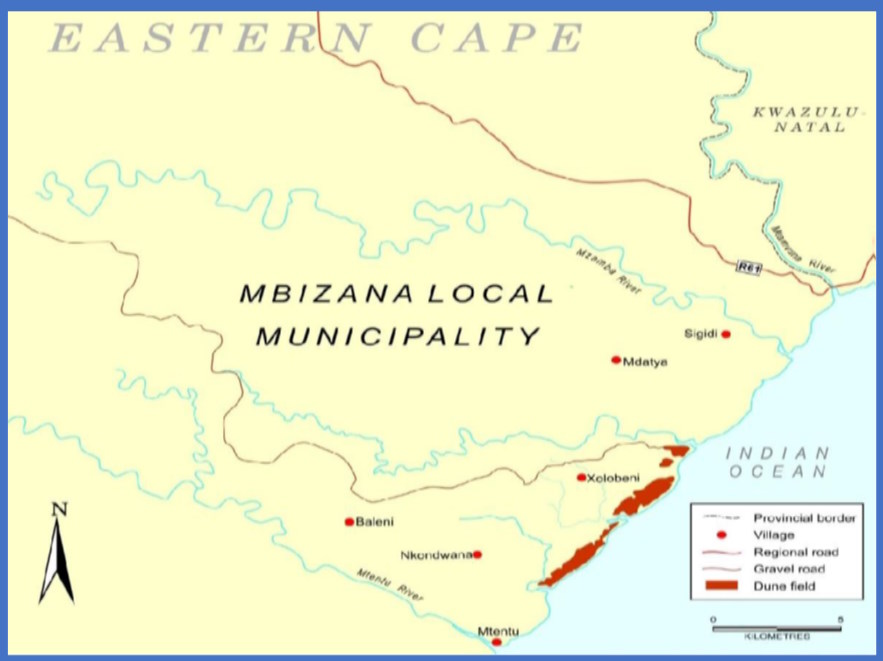

Xolobeni, on South Africa’s Wild Coast in the Eastern Cape, is renowned as a biodiversity hotspot. It’s also known for its community activism against mining, and in defense of customary land rights and sustainable rural livelihoods.

It is perhaps less well known for the achievements of organized local civil society in protecting and developing the commons as the basis of the area’s sustainable, equitable rural economy. The Amadiba Crisis Committee (ACC), the main community organisation representing coastal residents, has won precedent-setting legal victories against powerful extractivist interests.

The community’s Right to Say No to mining by Australian firm MRC was affirmed in a High Court ruling in 2018. Then, in 2021, Shell was interdicted against conducting seismic testing for offshore oil and gas.

While the courts have recognized the peoples’ rights to developmental self-determination, the state has refused to do so, insisting that coastal communities are poor and that mining is the only pathway to ‘development’.

This is a narrative that coastal residents reject unequivocally. Instead, they point to their rich, communal, agrarian history, and success with developing eco-tourism and small-scale organic farming. These gains have been made without support from the state, and amidst evidence of sabotage by politically connected local elites.

The images and video/audio clips in this story were taken as part of an ongoing collaboration that began in 2020 between the ACC, and geographers at the University of Johannesburg, and the University of KwaZulu Natal.

These photos were co-curated with the ACC to showcase their alternative commons-based approach to development, and its potential to deliver genuinely sustainable, equitable development outcomes in Xolobeni – and beyond.

Click the play button beneath each image to hear an audio description in isiMpondo, a language commonly spoken in Xolobeni.

The story of commoning in Xolobeni

There is a long history of commoning in Xolobeni. During the Mpondo Revolts in the 1950s and 1960s, villagers resisted dispossession and enclosure under Apartheid-era ‘betterment’ programmes.

Hiding in caves, fighters established secret food crops to sustain them in their struggle.

The Mqongeni caves in Bekela village are scattered with seashells that, according to local guides Nontlakanipho Mthwa and Tamara Mthwa, were used as eating utensils by fighters in hiding during the Revolts.

(Photo: Mbekezele Mbuthuma)

Apartheid may have ended, but the human rights of these communities continue to be violated, now by the extractivist state and its powerful corporate allies.

Despite significant legal victories blocking titanium mining, an unwanted coastal highway, and seismic testing for oil and gas, authorities at all levels continue to promote unwanted top-down projects, insisting the communities of Xolobeni are ‘poor’ and need ‘development’.

This is a narrative the people of Xolobeni reject — they argue: “As long as the people have land, they are rich.” Land is central to livelihoods here, and is governed through practices of direct democracy and consensus-based decision making.

Final decisions on land use are made at Komkhulu, or the Great Place – the seat of traditional authority – but only after extensive consultations with all community members.

(Photo: Nonhle Mbuthuma)

Land-based livelihoods: Ecotourism

Many livelihoods have been built around eco-tourism, as Xolobeni is extremely rich in biodiversity and endemic plant life.

Lonwabo Dlamini is a tour guide and resident of Sigidi. As well as sharing his detailed knowledge of medicinal plants, geographical /geological features, and local culture and history, an important part of his work includes reporting fishing out of season and vehicles driving on the protected shores.

The Khwanyana Lodge is a new eco-tourism facility under construction in Mpindweni village that will be entirely owned and run by community members. Its construction is being funded by dividends from the Mtentu Lodge, a privately owned business that operates on communal land owned by the people of Xolobeni. According to local guide Zama Mthwa, the new lodge will open in May 2024. (Photos: Hali Healy)

There are several sites of historic and cultural importance in the area, from shipwrecks, to graves, and archaeological sites.

Esimbovu (named after the red colour of the dunes) in Nyavini hosts tools that date back to the early and middle stone ages. Local guide Zama Mthwa says: “As people who live here it is our responsibility to ensure that our archeological sites are protected and conserved, so everyone has a role to play so the artifacts remain there.”

The red dunes that stretch along the coast are in themselves a spectacular sight to behold, drawing many tourists who hike the area annually. This was the first time Mbekezeli Mbuthuma, a resident of Sigidi village, had been to this part of the dunes near Mpindweni.

The protea is South Africa’s national flower. Across Xolobeni vast fields of wild protea draw numerous tourists and so are carefully protected by local guides. This year guides observed that the fields have been slow to bloom, attributing the delay to climate change.

(Photo: Zama Mthwa)

The Xolobeni region is home to countless pristine rivers, streams, waterfalls, and freshwater pools.

The Pushungwane pool near Mdatya village is an important site for tourism. According to guide Khumbulani Hlongwe, many visitors come here to swim and take scenic photographs, especially for weddings.

Land-based livelihoods: Pastoralism and agro-ecology

The Khwanyana community garden and indigenous seed farm is part of a new project in Mtolani. According to guide Nontlahla Mthwa, the project has already begun to host visitors who come to learn about agro-ecological food production in Xolobeni.

Many homesteads across Xolobeni raise cattle. Common grazing areas such as this one in Sigidi feature across the area. These are important in enabling children, who would otherwise be needed to help tending cattle, to attend school. It’s not unusual to see cows cooling off in estuaries or on beaches.

Wetlands feature across the fertile landscape of Xolobeni, and are an important source of water for crops such as amadumbe, bananas and sugarcane. Cattle herders rely on the fruit of Waterberry trees in wetlands to stay hydrated during long days of herding. (Photo: Hali Healy)

This wetland in Mtolani, according to guide Khumbulani Hlongwe, is an important source of medicinal herbs for sangoma, or traditional healers.

(Photo: Hali Healy)

Community members collect yellow and black clay from stream beds throughout Xolobeni. The yellow clay found here in Bekela, explained guides Tamara Mthwa and Nontlakanipho Mthwa, is still used for making paint for the exterior of rondavels, the round houses found in many homesteads.

(Photo: Hali Healy)

Blockmaking for construction is also a vital livelihood activity. Breezeblocks made from readily accessible sand and water can be found stacked up ready for sale near many streams, like this one near Mdatya. (Photo: Hali Healy)

Uduli is a type of grass collected by women from wetlands and estuaries all over Xolobeni, like here in the Mphahlane estuary in Sigidi.

Uduli is dried and woven into hardy straw mats that are sold locally and to tourists. Bushels of dried grass are collected by women who sell it to brokers from Durban and surrounding areas of KwaZulu Natal, the neighbouring province.

(Left photo: Bev Ditsie / Right photo: Hali Healy)

Amadumbe, a type of yam, is grown organically and consumed locally as an important staple. Its plentiful yields mean the crops are also sold across South Africa, making their way as far North as Johannesburg.

Crops are planted and harvested collectively every year, providing an important source of income as well as sustenance for local communities.

So self-sufficient are the farmers of Xolobeni that they have become providers of food aid to vulnerable communities nearby, and further afield in the informal settlements of Durban.

Xolobeni has a number of highly biodiverse indigenous forests, from where fruit, medicinal herbs, firewood and building materials are collected.

The Mqongeni forest in Bekela, our guide Tamara Mthwa explained, is an important source of large strelitzia trunks, used for fencing around grazing areas and homestead gardens, and for building traditional storage containers for maize. (Photo: Hali Healy)

Looking forward

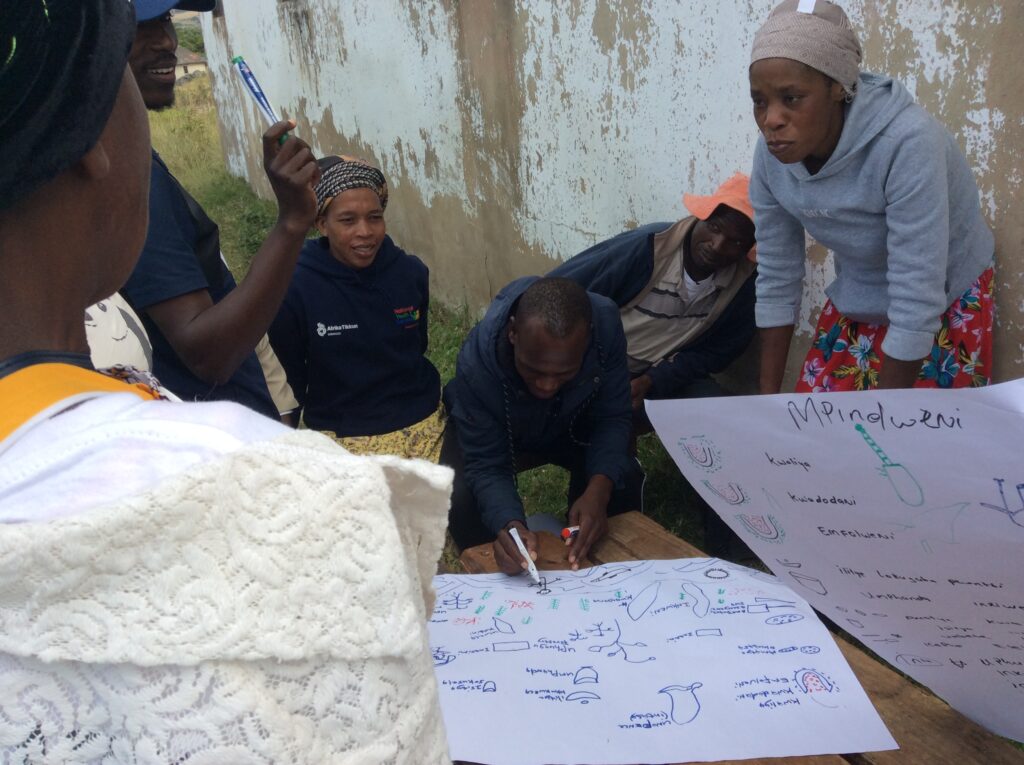

Politicians at all levels continue to try to impose top-down extractivist ‘development’ initiatives in Xolobeni. In response, communities have developed their own bottom-up strategy based on eco-tourism and agro-ecology.

In this workshop, Amadiba Crisis Committee members are mapping their own alternative development plan. They aim to convince publics and policy makers that a more equitable, sustainable future is not only possible, but already in the making. (Photo: Hali Healy)

About the author

Hali Healy is a political ecologist and Senior Lecturer of Development Studies at the University of Johannesburg (UJ). Since 2021 her research has focused on Xolobeni, where she has worked closely with the Amadiba Crisis Commitee. This photo essay was co-produced with the generous support of UJ’s University Research Committee, and South Africa’s National Research Foundation.

Learn more

Watch Hali Healy’s talk on Commoning in Xolobeni, given at the Masters in Commoning Administration short course in Bristol in September 2023.

Links

Amadiba Crisis Committee (Facebook page)