Mpox (previously known as monkeypox) was first ‘discovered’ in 1958, though it’s only in the past year that it’s gained significant international public attention. The disease can have very visible symptoms, with painful lesions that spread all over the body in more severe cases.

In 2022, there were almost 84,000 cases of mpox in 103 new countries, and it was declared a public health emergency of international concern. But several years before this, following clusters of cases in 2017, Nigerian scientists and public health officials had been sounding the alarm about mpox, the need to understand its epidemiology better, and the need for better public health strategies.

Mpox is considered endemic in Nigeria, but we still do not know a lot about it. In Nigeria, a country leading in public health approaches to respond to infectious diseases, there are still many uncertainties about patterns of disease and transmission. We’re also not sure how mpox has changed over the years: it used to be confined to rural areas, with a few cases here and there, typically connected to an animal source. But since 2017, we’ve seen it spread more widely, including from human to human and in urban areas.

From October 2022 to February 2023, a team of researchers[i] carried out studies in southwest Nigeria to explore the question: What is the story of mpox in the country? We wanted to find out what makes people vulnerable to the disease, and what aspects of the urban environment make it easier for mpox to spread. We wanted to look into pathways to care and treatment by people who have been affected. We also looked into the public health response to the disease in the country, to learn from the work of the Nigerian CDC (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) and the Ministry of Health.

As part of our research, we travelled to parts of Lagos, Ogun, and Oyo states that had been identified as having had a number of confirmed mpox cases in the last year. We conducted interviews with residents who had experienced mpox symptoms and those who treat them (from drug shop owners to herbalists and health workers).

This photo story explores how mpox is felt and understood by different people – including those with symptoms, the wider community and healthcare workers. It gives a snapshot of some of the themes from our research, though it’s not the whole story.

Who is living with mpox?

Confirmed mpox viral infection has shown up in all kinds of people in Nigeria: older and younger people, men and women, and those in both rural and urban areas.

Densely populated centres – such as in Lagos – are reporting higher numbers compared to the rest of the country.

Some people get symptoms that look like they might be mpox, but they are similar to the symptoms of chickenpox.

As testing and diagnosis aren’t available to everyone, people sometimes don’t know what they have, so are not sure what medicine or treatments to use.

The multi-country outbreak of mpox beyond West Africa was largely concentrated amongst gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Responses have also been directed at people seeking care for HIV, as Mpox can be more severe in people immunocompromised with poorly treated HIV.

In Nigeria, this has not really been the case, though it is an important and likely under-reported part of the story. In Nigeria, a Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill was signed into law in 2014, which prohibits marriage between persons of the same sex, as well as cohabitation and any “public show of same sex amorous relationships.” This reinforces the repressive environment for the LGBTQ+ community.

As part of our work, we interviewed men who identify as gay and had experience of mpox infection. Because of the vital role that civil society organisations (CSOs) play in healthcare in this context, these men were able to access care from LGBTQ+ serving organizations and places providing care for HIV. However, many also chose to isolate at home, worried about venturing out or seeking care.

How is mpox spreading in Lagos?

People we spoke to who live in Lagos said that they did not know how mpox was spreading, but thought it was likely to be caused by the dry weather.

They also speculated that the close proximity of living quarters in places like Idi Araba or Ajegunle could encourage the spread.

Some homes in parts of Lagos are connected through narrow alleyways, where people share things like washing up areas and places to hang clothes. Children also come together here to play. In these areas, better public health strategies may be needed. Many dwellings are single rooms, so people within a household are also in close contact when they’re at home. If someone’s infectious, it’s difficult for them to keep apart from other people, though residents described taking different measures to isolate a sick person in the home.

However, it’s not only at home that people can come into contact with mpox. Many people we spoke to with lab-confirmed mpox thought that they might have caught the disease on public transport.

The danfo (yellow minibus), a common feature of Lagos life, is often densely packed with goods and people.

People we interviewed also used this as a main form of transport from one hospital to another when seeking mpox care.

Traffic coming into the city is important too, in the eyes of people we talked to. Lagos is a hub of commerce: indeed, it’s the most important site economically in Nigeria, where trucks bring goods from all over the country to the port for shipments abroad. This also means a huge amount of human traffic, often through very densely populated areas.

Left: A sanitation and waste management hub in Lagos.

Right: Lines of petrol trucks waiting to enter Lagos

People we talked to also pointed to the lack of trash collections in their local area. In urban informal settlements, water and sanitation are main issues when speaking about infectious disease transmission.

For some, the lack of reliable waste collections and the build-up of rubbish were a potential source of disease outbreak, but also a sign of government neglect. Though these pictures were taken during the dry season, one can imagine the scene during the rainy season, and its resulting impact on people’s health.

Getting treatment and care

For people who have signs or symptoms of mpox, their first port of call may be a Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC).

However, there are a few factors that discourage people from going to a PHC. They include cost implications, long wait times, staff absences among health workers, and shortages of the right medicines. Because of this, many people will first seek care in a drug shop or pharmacy.

In Idi Araba, people we spoke to said that they would only go to a government health facility if the situation was dire, meaning that people aren’t getting basic care or essential prevention.

Furthermore, they also complained about the issue of the language barrier which hinders them from visiting the PHC. Instead, many choose to visit Hausa-speaking medicine sellers who will render their services and even provide medicines on credit.

The Primary Healthcare Centre in Alimosho Local Government Area, in northern Lagos.

This assistant and trainee works in a pharmacy run by Mr Abdulrahaman in Idi Araba. Their shop provides critical care to people in the area.

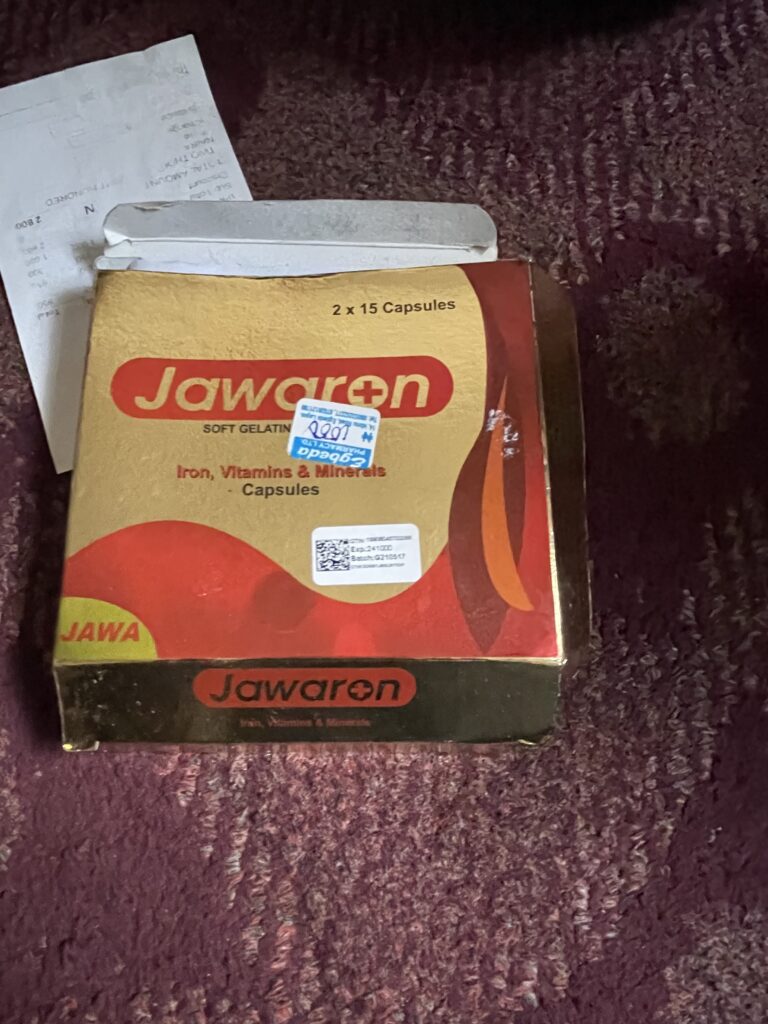

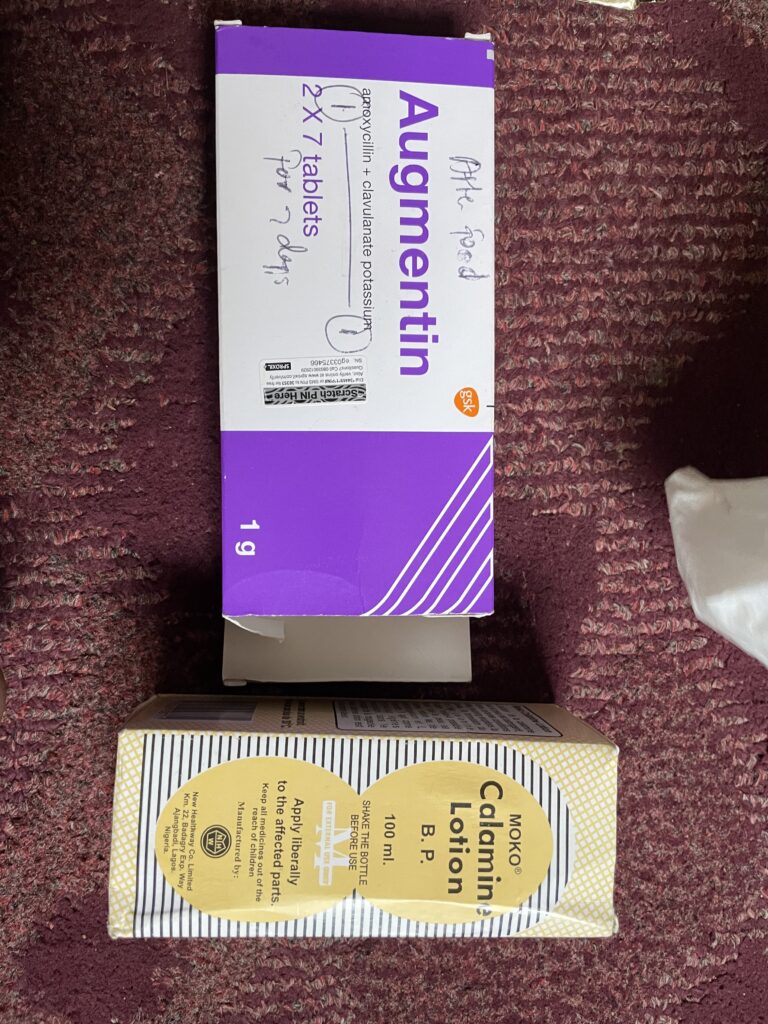

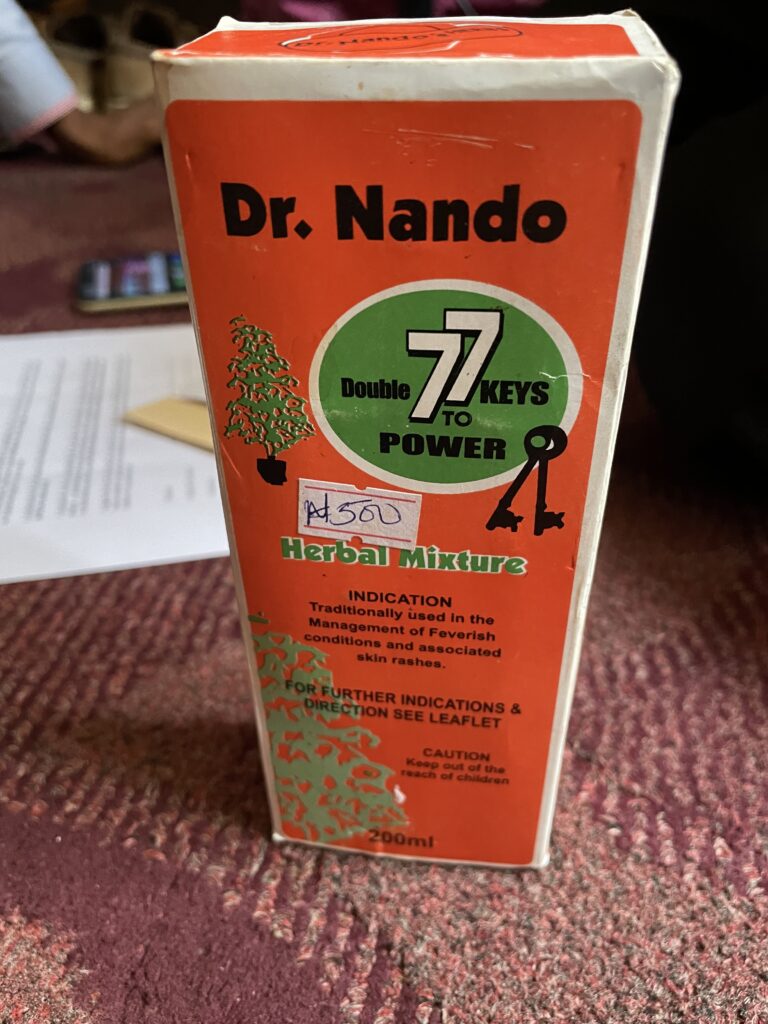

People with symptoms of mpox turn to various different forms of relief, including over-the-counter medicines and popular remedies.

Antibiotics, vitamins and calamine lotion are among the treatments people may get from pharmacies.

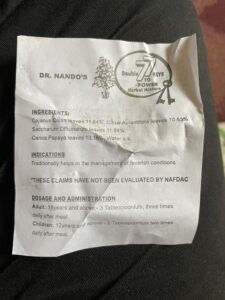

A vast majority of people we spoke to with suspected or confirmed cases of mpox rely on Dr. Nando’s 7 Keys remedy, to relieve itching. For some, 7 Keys will help to ‘bring the infection out’ of the body. They believe that otherwise the infection would remain ‘stuck’ in a person’s blood, and they will not be able to heal.

Herbalists are an essential source of care, drawing on rich Yoruba and Hausa traditions to provide specialist knowledge to patients and more whole-of-body healing.

Yoruba traditions and mpox

Public health understandings about controlling diseases like mpox that are linked to animal-human contact often focus on wild animal hunters, sellers of ‘bushmeat’ (meat from wild animals), and people trading in medicinal animal products.

Yoruba traditions also teach that wild animals, sourced from the bush, are a healthier source of protein than what is found in the supermarket. Bushmeat sellers argue that wild animals feed on organic plants, which build up their immune systems and make them more resistant to disease.

Bushmeat sellers point to our modern, processed diets as a source of disease: eating bushmeat is considered a way to be healthy by those who adhere to these traditions.

Bushmeat hunters and sellers feel targeted by government messaging that blames them anytime there is an outbreak. They felt like they were blamed for the spread of mpox early in the 2017 outbreak. (Photo: Olufunke Adegoke)

Improving the response to infectious diseases

As with other outbreaks and epidemics, people and communities develop their own strategies to respond to disease, supported (to a greater or lesser extent) by states and community-based organisations.

Responding to mpox will require building on Nigeria’s strengths, especially through the NCDC which is a model for epidemic response. It will also require tailored community-centered solutions and systemic shifts in how primary care is funded and prioritised. Primary care is the bedrock of any public health system.

The example of Lagos shows that mpox plays out in quite particular ways in urban areas. This isn’t just about how closely people live together: it’s also about how people get around, and what facilities are available. Poverty, gender and socioeconomic status affect how vulnerable people are to infection and more severe forms of mpox.

How people get and share information is important for staying safe and reducing the spread of disease. For example, it’s possible that the general public in Nigeria have become more aware of infectious diseases because they’ve seen more visible surveillance being carried out by local primary care health workers. The experience of Covid-19 may have also helped to focus people’s attention on the need to report infectious disease to help stop it spreading.

In Nigeria, just as in many places around the world, the way people understand and think of mpox matters. This affects the treatments they turn to, and the strategies they use to protect themselves.

Taking account of this in local, national and global health strategies will be vital for the future of epidemic response.

Photo credit and authorship

All photos are by Megan Schmidt-Sane, except where otherwise indicated. The text is by Megan Schmidt-Sane, Olufunke Adegoke and Nathan Oxley.

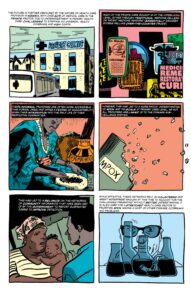

Related: Comic – Mpox in Nigeria: lessons from diverse experiences

Nigeria has invested in coordination, research and testing facilities to respond to Mpox. But while the health sector is fragmented, consistent surveillance and detection will remain difficult. Meanwhile, access to resources like vaccines and other important resources is still unequal around the world.

In this comic, we explore the wider lessons from Nigeria’s experience. Outbreaks of viruses can take very different forms in different places, and emerging or shifting outbreaks should be addressed sooner rather than later.

[i] The research project ‘The multi-country monkeypox outbreak: livelihoods, vulnerability and preparedness’ was carried out by an interdisciplinary team including social science and public health expertise from University of Ibadan and the Institute of Development Studies. The IDS researchers are Prof. Hayley Macgregor (PI), Dr. Syed Abbas, Dr. Megan Schmidt-Sane, and the researchers from University of Ibadan are Prof. Ayodele Jegede (Lead Investigator, Nigeria), Dr. Akanni Lawanson and Dr. Olufunke Adegoke. The project is funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).