Campaigners for the right to roam in England have generated a flurry of headlines from their most recent trespasses: one this month on the Englefield estate of the Minister for ‘access to nature’ Richard Benyon, and last month near Bristol, on the Duke of Beaufort’s 52,000-acre Badminton estate.

The Right to Roam campaign points out the absurdity of England’s laws that govern people’s access to land, and the history of the carving up of commons among a small group of landowning elites. Looking behind the fences is a reminder of the vast accumulations of wealth that exist alongside the everyday struggles of many people in towns and the countryside.

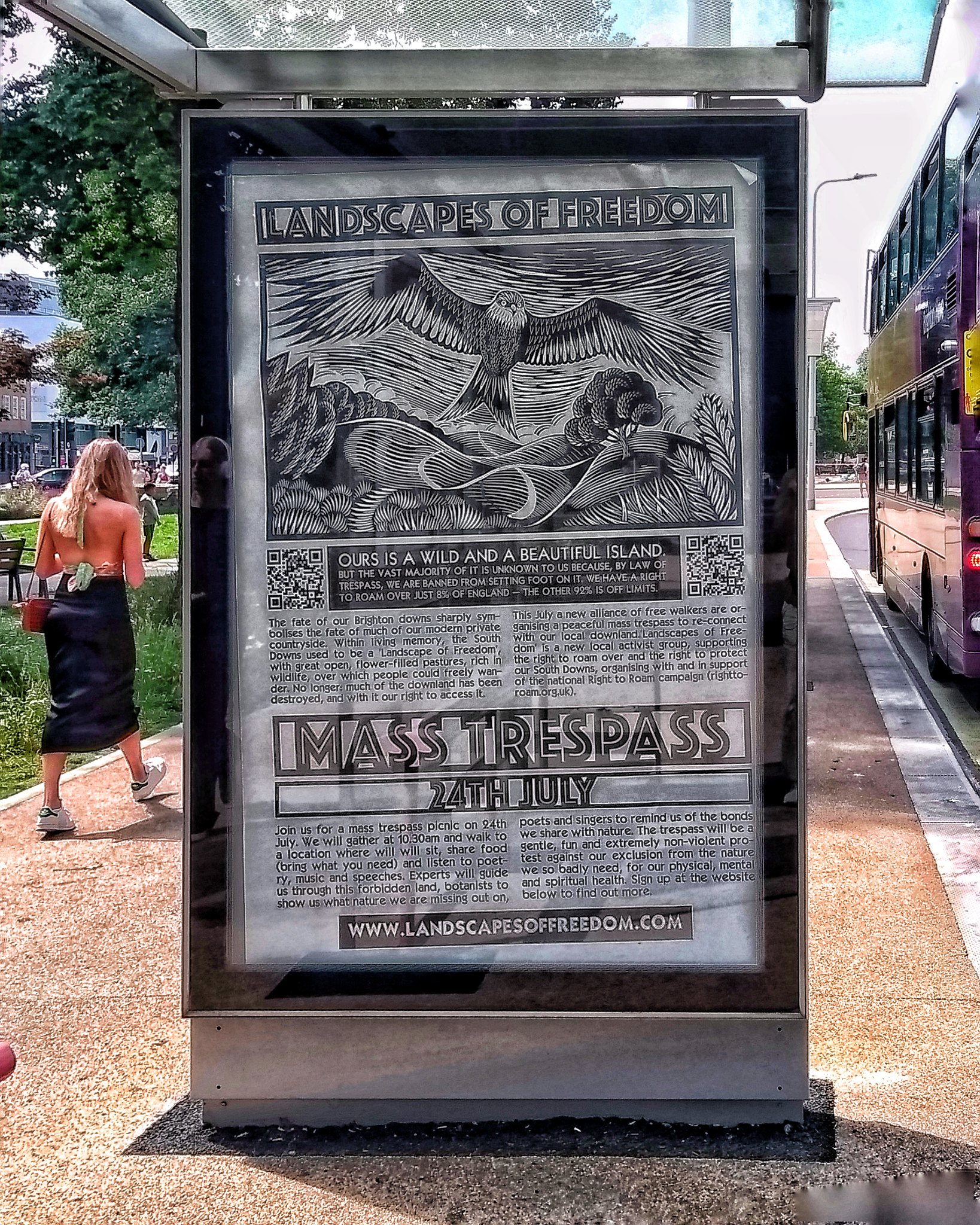

Right to Roam and Landscapes of Freedom weave different themes into expeditions. In Bristol, a central theme was botany and the chance to get up close to plants. The Englefield trip incorporated Morris dancing, pointing to unruly rural English folk traditions.

These themes demonstrate the campaigners’ appeal to the heart as well as the head. They identify rural commons (and the no-longer-commons) as sites for enjoyment, fun and creativity, alongside the more serious aim of observing what’s going on in nature behind the barbed wire fences. The attitude is sometimes confrontational and often playful; and the messages emphasise the aim to be inclusive and to welcome new participants.

In The Book of Trespass, Nick Hayes documents a series of walks in and around English private estates, charting the story of the dispossession, both legal and illegal, of rural people from commons over the centuries. The book tells a history of conquest, where money from violence and domination has sometimes been transformed into beautiful landscapes and architecture. No wonder the efforts of some historians to show the links between country houses and slavery have been met with such bitter resistance.

On his walks and overnight stays on country estates, Hayes also drinks in the atmosphere of rivers, paths and woodlands that turn still and spooky after dark. On occasion, he finds trespass to be a spiritual experience. Connecting with the land, the woods and the water isn’t just a practical exercise. It’s also about reimagining your own being in relation to non-human worlds.

The black-and-white illustrations dotted throughout the book conjure up the stark shadows of a moonlit night, or a snapshot of an animal caught in movement, while the style evokes the uncanny unreality of “an old English 1930s utopia that never existed… a sort of surrealist pastoralism”. These pictures aren’t just decorative. They’re part of the practice of going into the fenced-off land, where Hayes sits and sketches what he sees: it’s another way to be in a place and really pay attention to it.

By crossing the line, venturing away from the footpath and over the fence, intentional acts of trespass might encourage us to question rules and conventions that have become so commonplace they’re almost invisible. In his project Who Owns England, Guy Shrubsole has brought to light the hidden or hard-to-find details of land ownership by meticulously exploring the subsidies and structures holding up a system of land concentration whereby just 25,000 landowners– “typically members of the aristocracy and corporations” – control half of the country. But another kind of detail is out there to be found: the reality of woods, fields and rivers that can be touched and experienced directly.

By venturing into lands normally beyond reach, trespassers can provide a focus for outrage, while also reminding people of the joy and necessity of connection with the land around them. They also remind us that trespassing is all too often not a free choice: one example is the ever-tightening restrictions on the ability of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities to move around freely and safely.

They also raise other questions: what are the other enclosures – in cities, in work, in everyday life – that are quietly accepted or ignored? What other ways are there to hop over fences – physical or otherwise – and reconnect with what has been lost or taken? What lessons can be learnt from other sites of resistance, and in other parts of the world, where bitter struggles are fought to defend commons, and what further connections could be made between them?

Image: Dominic Alves (cc by 2.0) / https://flic.kr/p/2mdb231