Power and contestation

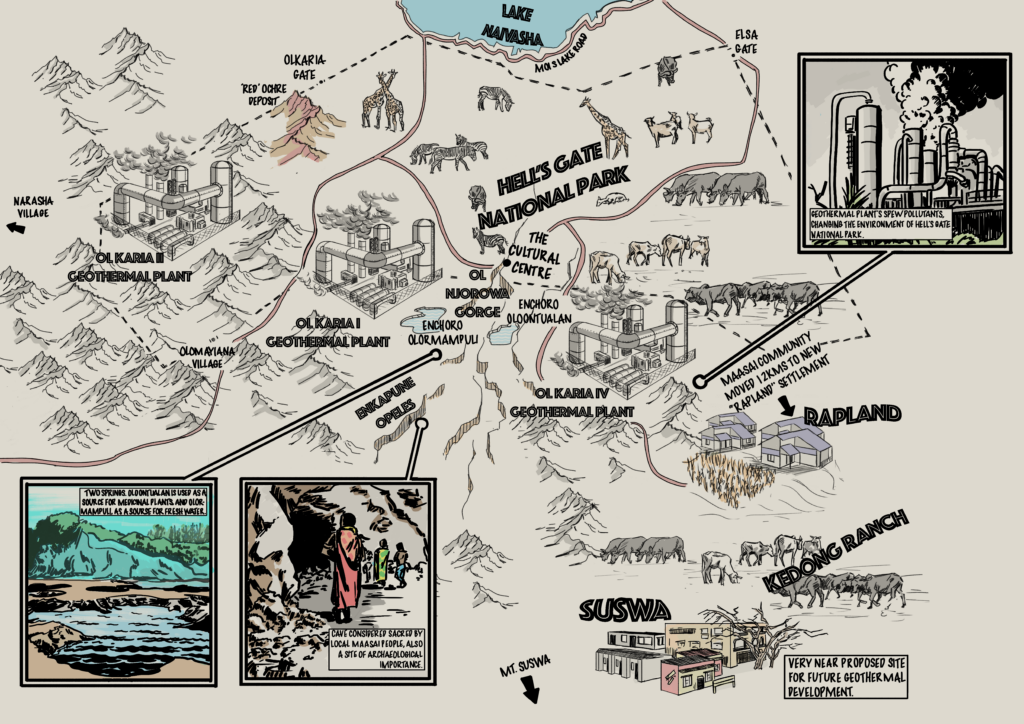

Geothermal power generation in Kenya is being massively expanded – funded in part by the World Bank and European Investment Bank (EIB).

While it is seen as vital to the country’s future prosperity, and welcomed by political and business leaders, it has had severe environmental impacts, resulted in the displacement of Maasai and other residents, and created new divisions and tensions within local communities.

What are the socio-cultural-economic impacts on, and conflicts involving, Ol Karia’s various community-level stakeholders?

The population of Ol Karia is about 20,000, living in scattered villages.

While residents are mainly Maasai, members of other ethnic groups live here too, including Turkana, Samburu and Kikuyu (who have long intermarried with Maasai).

The predominant Maasai socio-territorial section is Keekonyokie. Many people practise pastoralism (keeping cows, sheep and goats), but livelihoods have diversified in recent years.

People now also work, for example, as traders, labourers, tour guides, sellers of beadwork and curios to tourists, charcoal burners, blacksmiths, and for geothermal companies.

Jobs with these companies are often low-paid and casual; young people in particular complain that the best jobs go to non-Maasai.

Most people do not have land title, a major grievance that leaves them vulnerable to land-grabbers and forced eviction to make way for geothermal plants.

There are few health clinics, and the nearest public hospital is in Naivasha (40kms or more away).

Residents have to pass through Hell’s Gate National Park to reach Ol Karia from nearby towns.

Transport is infrequent and expensive, forcing people to walk 15kms or more to services and work.

Geothermal industry has contaminated water supplies, and led to soil erosion and gullies into which cows often fall.

The air around the plants stinks of hydrogen sulphide, a gas that seems to cause respiratory and other ailments.

Scramble for steam: The hard story of power and displacement

As geothermal industry has multiplied in Ol Karia in recent years, so too have consequences for residents.

Maasai were forcibly evicted at various times, most recently in August 2014, to make way for new plants.

One thousand members of the Ol Karia sub-section (ol-karia means ochre in the Maa language) were displaced and re-settled in RAPland (RAP stands for Resettlement Action Plan), a new purpose-built village 15 kms away from where they were living previously.

While this village appears ‘modern’, it lies on land unsuitable for livestock or agriculture, and lacks basic amenities.

Electricity connections have come at great cost (unaffordable to many) and the provision of water from various tanks requires walking long distances for some.

Residents contested the erection of a perimeter fence – a move that severely restricts livestock movements.

The displaced have lost important cultural resources including sacred sites and ancestral graves, which they can no longer access, and are struggling to sell home-made crafts to tourists – an important livelihood for women.

“Only a rich man can survive here”

Fatuma Hitler, a feisty Samburu woman living in the village of RAPland, a new village for Maasai who were moved to make way for geothermal development.

Learning from the ground up

Since late 2017, our research team has investigated the various perceptions and experiences of geothermal development amongst residents of Ol Karia, covering the villages of Narasha, Olomayiana Kubwa, Suswa, and RAPland. Our work combined qualitative techniques with historical analysis and community-based participatory research.

We trained Maasai facilitators to lead local stakeholder groups in using participatory research and analysis activities, interviewing, and participatory video. Group participants included women, young people, elders, herders, workers, school leavers, and businesspeople.

Video was used to record highlights from participatory exercises, such as resource mapping, livelihood trendlines, and public attitudes to geothermal development. Videos were played back to area residents to share experiences and aid reflection and synthesis.

This helped team members to identify key themes for further creative video-making exercises. More than 100 hours of video material was generated and analysed.

Here are a few of the videos created through these participatory processes.

For more information on the Seeing Conflict project, please visit the project page on the IDS website.