In July 2022, the Ecology and Society Workshop (ECOSOC) at the University of Coimbra, Portugal hosted its first summer school entitled The Pluriverse of Eco-social Justice. It was a carefully curated space to “co-learn and co-produce knowledge and insurgent research-action around themes of environmental (in)justice, the commons, anti-colonialism and emancipatory pedagogies”.

The school had a strong emphasis on commoning, so I felt moved to reflect on some encounters with two key dimensions of commoning that Future Natures organises around: “culture, knowledge and technology” and “nature and natural resources”.

Artistic commoning and the Livros Cartoneros movement

Our encounter with an example of artistic commoning in Coimbra began with a workshop inspired by the Livros Cartoneros (‘cardboard books’) movement. The workshop took place in a cultural association called Casa da Esquina (‘House on the Corner’). Located in an old but brightly salmon-coloured mansion house, Casa da Esquina began in response to the 2010-14 financial crisis in Portugal. The homeowners opened their doors to the public as a space for those disaffected by the crisis to engage with art. Today, it’s a refuge for artistic commoning. But what does that look like in practice?

Artistic commoning enables artists to access the resources (like materials or spaces) necessary to produce art via alternative labour networks and economies based on cooperation, collaboration, mutuality, and co-creation. It presents a cultural response and contestation to the marginalisation of people with less capital and limited means to produce and/or enjoy or participate in artwork. For example, the United States based HowlRound Theatre Commons group considers theatre-making not just an art form but that it produces knowledge which is a non-rivalrous shared resource. As such, HowlRound advocates practices that “promote relationality, cooperation, horizontal and decentralized decision-making and networks, bottom-up activity, and peer-to-peer sharing of infrastructure, material goods, knowledge, and ideas”.

In Coimbra, knowledge, technology, tools and other materials are shared so that the city’s residents can access the means to engage in digital art, photography and crafts without monetary cost. Instead, Casa da Esquina functions through ‘a system of solidarity exchanges in which the exchange currency is time.’ Those wishing to use the space can do so freely in exchange for volunteering part of their time to carry out the necessary tasks to keep Casa da Esquina going.

Casa da Esquina also supports the Livros Cartoneros movement. First emerging in Argentina in 2003, Livros Cartoneros sprung out of discontent and national mobilisations against austerity; a period in which many people became waste pickers collecting cardboard to recycle (known as the cartoneros). Meanwhile, the publishing industry had become increasingly centralised, concentrated, and captured by market and political forces.

Faced with the struggle to make their literature accessible to the country’s unemployed population, some writers started to engage with the self-production of books using recycled cardboard, string and paper. Livros Cartoneros enabled people to produce low-cost books which bypassed the publishing marketing system, making the production of literature and the reading of lesser-known authors more accessible, whilst creating support for the self-managed recycling networks of cartoneros.

As such, today this movement has reached over 21 countries with around 250 collectives in Latin America alone. Particularly popular in Brazil and Mexico, groups such as Pensaré Cartoneras are able to share knowledge which is otherwise devalued, silenced or peripheralised by mainstream publishing and the ‘Eurocentric canon’: themes relating to feminism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism or autonomous and land struggles.

Livros Cartoneros presents a form of commons production, by creating spaces to “re-appropriate what was already ours: the word”, by building more egalitarian and solidaristic forms of political, social, and economic organisation through experimental alternatives to transnational publishing corporations. Whilst the latter enclose, privatise and commodify literature, the Cartoneros movement mobilises the ethos and logic of solidarity economics which ultimately produces knowledge for the many rather than the few. This kind of commoning of resources focuses on needs-provision, whether that be for waste collectors or writers, rather than on profit-accumulation.

A particularly curious part of this movement is how it provides a network of people with collaborative, commoning work in part by reclaiming discarded waste as a common resource. Challenging the capitalist view of waste as something void of use value, reclaimed cardboard becomes a valuable resource to produce literature in a more accessible way. Despite encountering many difficulties, the Livros Cartoneros movement is based on a reorganisation of a workforce understood as capable of gaining more autonomy over the means of production; creating its own living conditions; its own way of life-making. In so doing, it presents an example (not without its contradictions) of commoning.

Life beyond plantation capitalism: Forest commoning in a world on fire at Baldio do Serpins

During the summer school, Portugal was experiencing one of several severe heat waves to hit the country in 2022. As temperatures reached 43 degrees Celsius in some areas, the entanglement between the commodification of forests for the eucalyptus industry and the increasing threat of wildfires in the context of the climate crisis, became starkly evident.

The rural landscapes surrounding Coimbra are layered with histories of enclosure and of struggles to assert forests as a commons. The work of Andrea Nightingale is useful in helping explain what it means to treat a forest ecosystem as a commons, rather than a private entity for accumulation. The becoming of forests as a commons and people as commoners happens through a set of practices and performances that foster new ecosocial relations. These relations don’t happen through the technical management of resources but from emotional ties to them, to place and community, which are further developed when a resource is stewarded collectively.

The summer school showed us that to assert collective property rights over a forest was to fly in the face of a dominant legal and economic regime that allows forests to be controlled by private property rights which- in the case of eucalyptus plantations- has devastating consequences.

The second day of the summer school, we took to the Mondego River where, amongst other forms of extractivism, we learnt of one of Portugal’s most pervasive extractive industries; that of eucalyptus production. Moored on a sand bank, our guides gave us a verbal tour of Portugal’s eucalyptus industry, accompanied by the unmistakable cracking sound of tree trunks being severed which echoed throughout the valley. In the background, we could see eucalyptus trees being felled on a steep-sides slope, the soil sediment crumbled away and descended straight down into the riverbed leaving behind a desolate bank.

The Eucalyptus globulus makes up 26.2% of all forest cover in Portugal –more than 800,000 hectares, the largest area in all of Europe– and is a fast-growing tree with hugely negative impacts on the local soil ecology and biodiversity. The first commercial plantations of eucalyptus were established in the late 1800s, and expanded significantly during the fascist regime of 1933-1974 which took control over common lands (baldios), Through these processes, eucalyptus trees have replaced rich and biodiverse ecological systems and, in part because of their flammable oils, are prone to catching alight in summer months. The increasing frequency and scale of wildfires will undoubtedly increase with climate breakdown.

The industrial planting of eucalyptus also agitated many peasants whose use of the land for agrarian purposes was often encroached on or appropriated by eucalyptus plantations. These enclosures were not without protest. In 1989 for example, 800 people gathered in a small village in Valpaços to resist a state-backed corporate plantation of eucalyptus for commercial production. This was one of Portugal’s largest environmental protests at the time, during which community members uprooted eucalyptus seedlings overnight. This community won its battle, but the persistence of ecological imperialism continues today, as do the struggles against it.

The same company which attempted to enclose Valpaços in the 80’s evolved into a larger conglomerate, which has since exported its eucalyptus plantation model onto Mozambique. There, eucalyptus is being grown in the name of forest restoration for climate change mitigation. In reality, this has been referred to as a ‘neo-colonial project’ that is ‘usurping the land and livelihoods of thousands of peasant families’ to produce trees for paper and pulp destined for Portugal.

In sharp contrast to the corporate capture of land for ecocidal plantations, our visit to Serpins, a small village in Lousã, presented an altogether different model for reproducing treescapes. This village was home to self-identified ‘commoners’, many of whom had been intergenerationally stewarding a nearby woodland which is formally recognised by the state as a ‘common’ forest.

After giving us an informative talk, one of the commoners went to his car and came back with a box full of wooden pegs. These pegs, made from wood from cork oak trees collected from the Baldio do Serpins were carved by his father to hold together old beehives. In Portugal, Baldios refers to land located mostly in mountain areas which – including the plants, bushes and trees growing upon it – is considered a common good and access to them a common right.

When the Portuguese dictatorship ended in 1974, swathes of rural land were returned to those who claimed them. These people were referred to as the Comunidades de Compartes (commoners). The commoners regained the right to govern which in most cases involved attempts at direct democracy, reinforced by law and recognised (although often denied) by the state organisations. Serpins is one of the most recent examples of a community to exercise their right to govern the land as a common property system, as up until 2016 it was delegated to the municipal authorities.

Similar to the New Forest Commons in England, the right to be considered a ‘commoner’ is not a birth right or inheritable right to soil. Instead, ‘citizenship’ to these territories is granted to all residents based on them inhabiting or ‘occupying’ the area. They are then able to participate in the administration of the common lands by attending and voting in the commoners’ assemblies.

Sitting beneath the shade of a cork oak tree, we noticed a haze of smoke descending from the hillsides; a wildfire had broken out nearby. Serpins felt like an island of resistance in a world on fire. Amongst a sea of eucalyptus plantations owned by powerful corporations, the forest commons offered respite from the logic which values forests as lifeless sites of unfettered extraction.

Commoning other worlds against and beyond neoliberal capitalism

Both the Livros Carteneros movement and the Baldios are examples of everyday life-making beyond a neoliberal capitalist society. They offer alternatives to the march of privatisation and the logics of neoliberal individualisation. Moreover, they help us to imagine “a world where many worlds fit” (to borrow from The Zapatista movement). Needs-oriented models of work, exchange, production, distribution, and ownership aid communities to “live with dignity as a form of resistance and re-existence”. These examples I have explored reproduce themselves despite ongoing pressures applied by an economic system which makes it hard for many to imagine a society based on cooperation, solidarity and care. But the commons are the foundation of the other worlds we know are possible; and it takes communities who care enough to create, maintain, and protect them.

This article was also posted on the Undisciplined Environments blog.

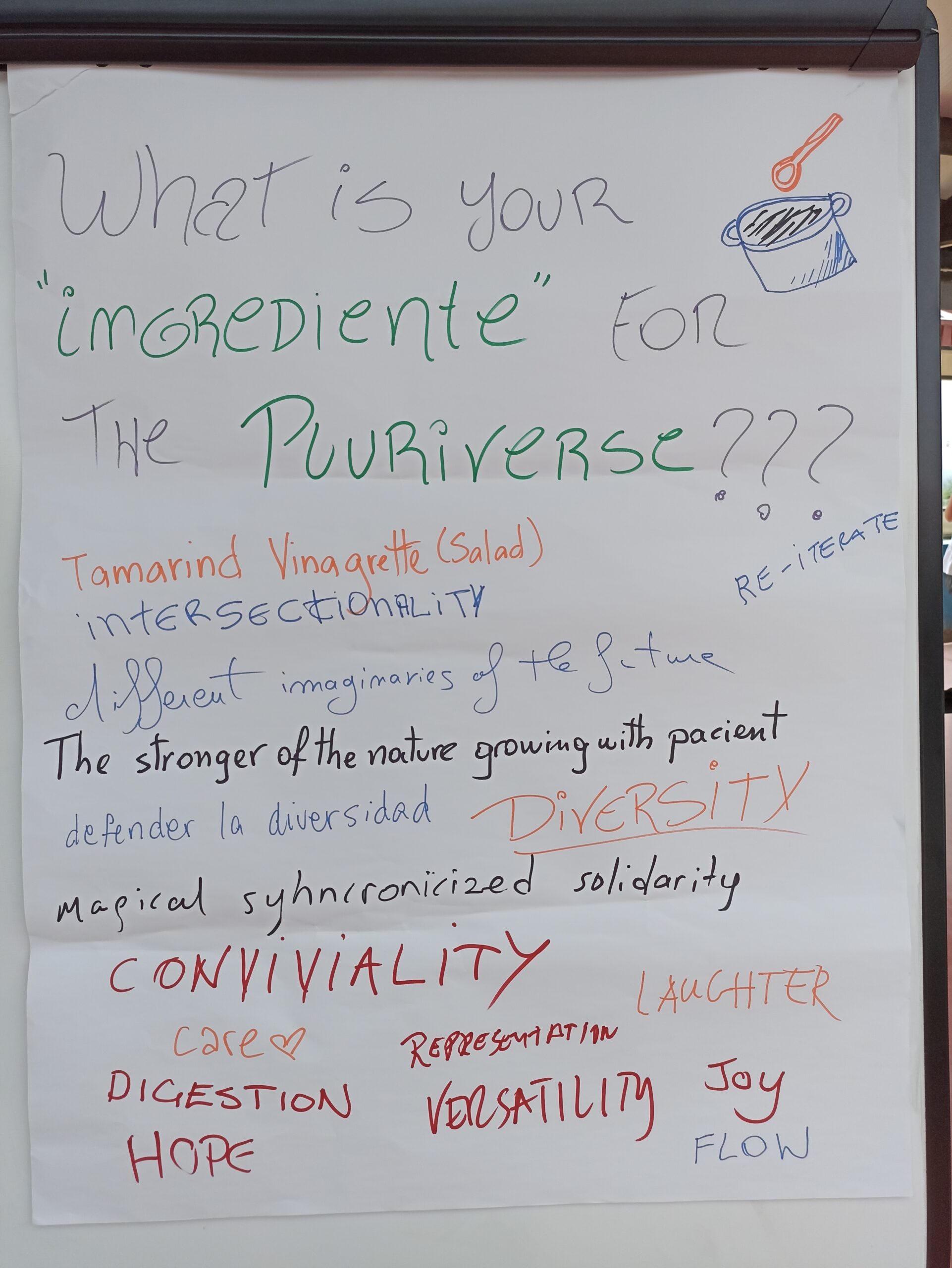

Header image: Collective collage of ingredients of the Pluriverse, created by participants on the first day of the Summer School as part of a collaborative rice excercise led by José João Rodrigues of Casa do Sal (July 11, 2022).