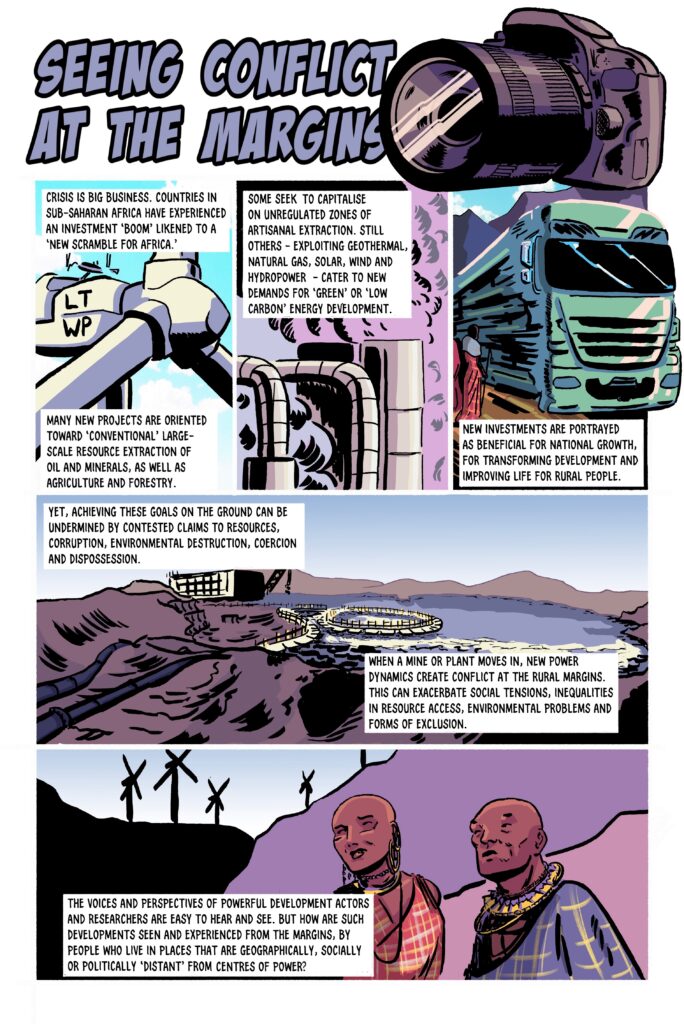

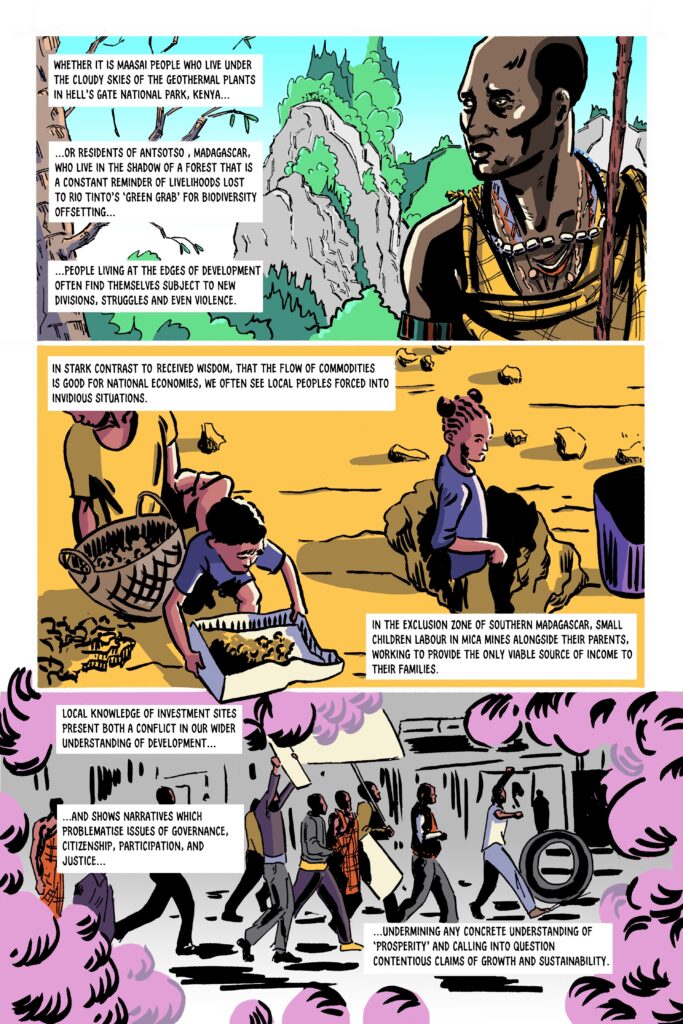

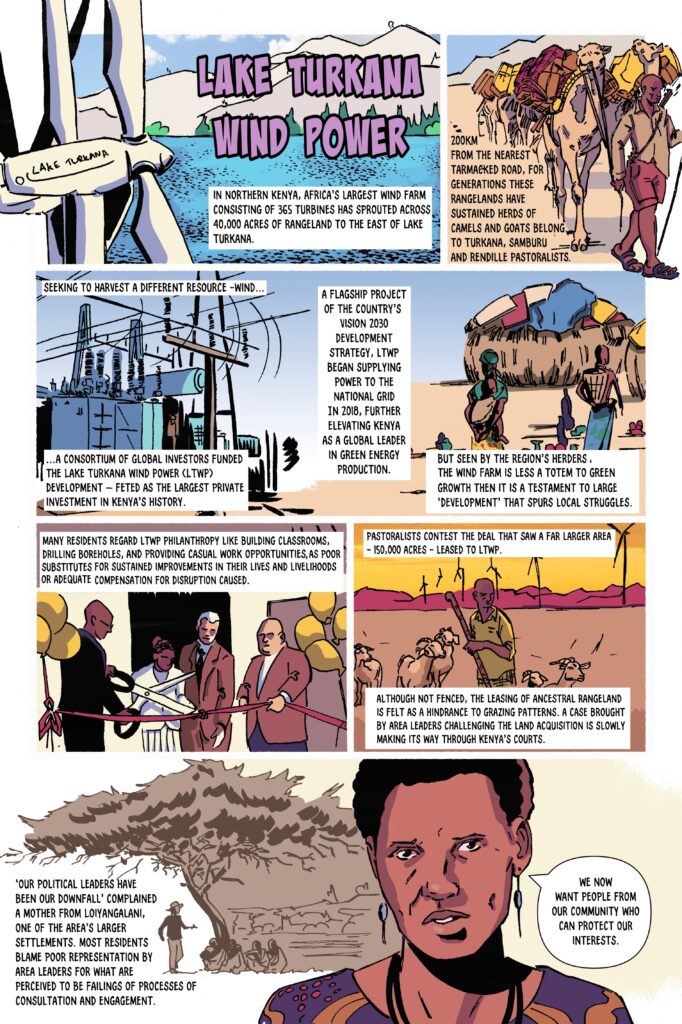

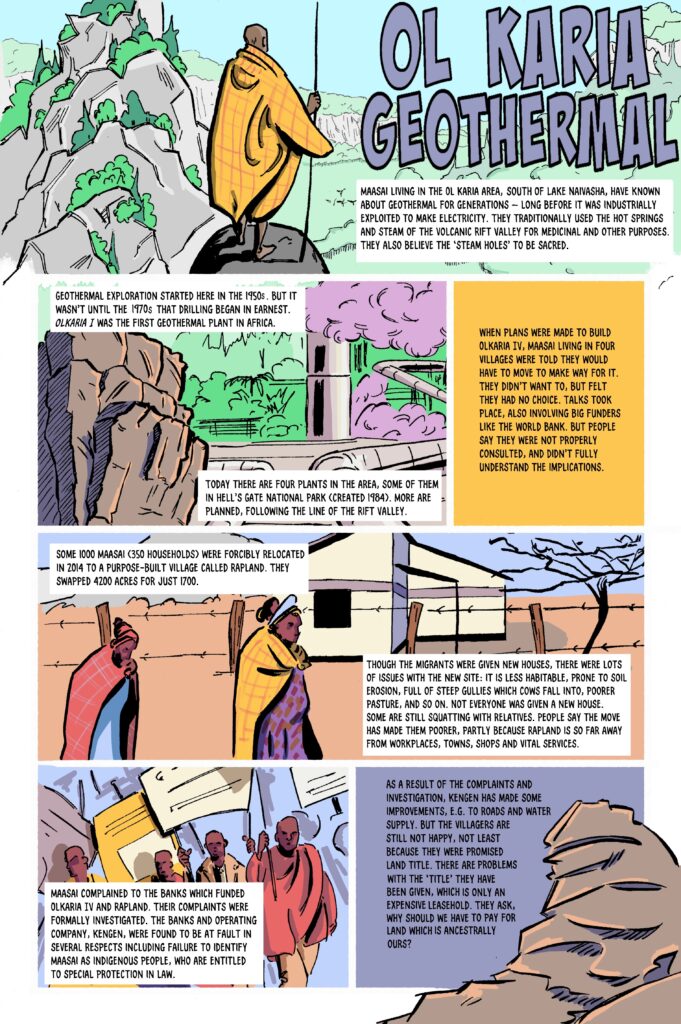

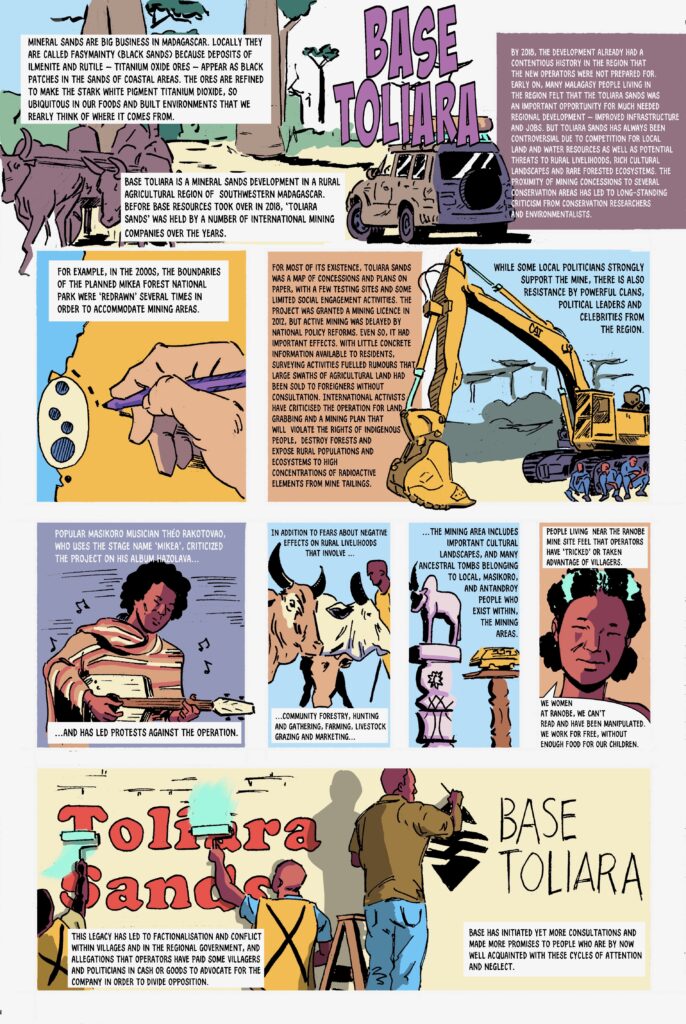

Large-scale resource developments can create ruptures at the margins that intensify long-standing struggles around livelihoods, public authority, and environmental justice, and in some cases can spark new tensions and conflicts.

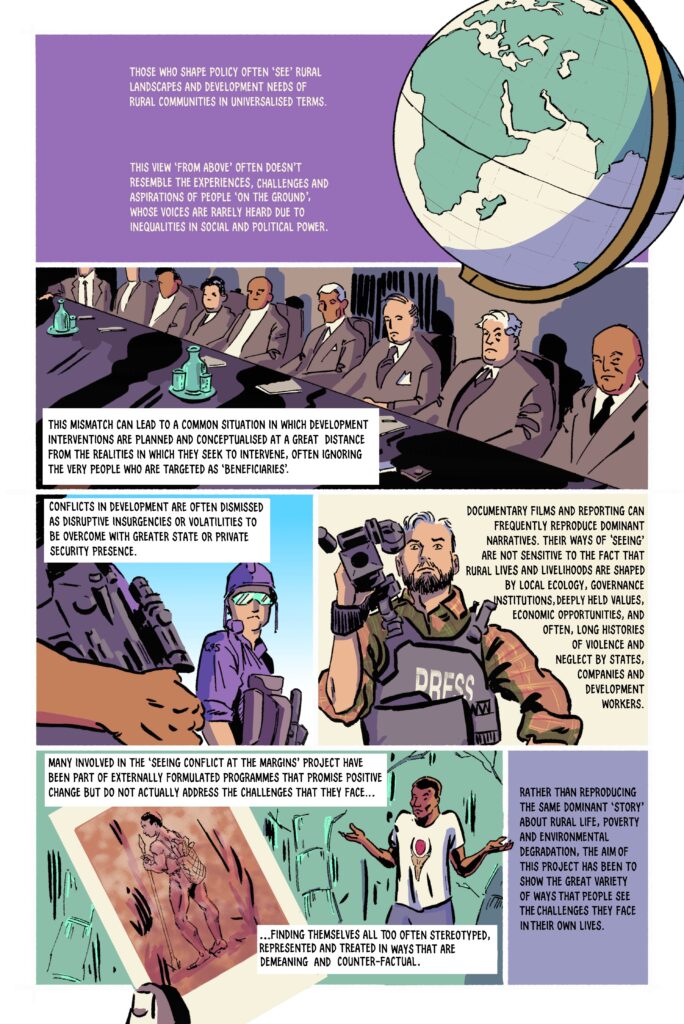

Ordinary people experience and talk about resource conflict, well-being, and aspirations for the future in ways that differ – sometimes radically – from the dominant narratives of states and investors, and indeed from the unversalised conceptions of ‘security’ and ‘development’ that guide policy.

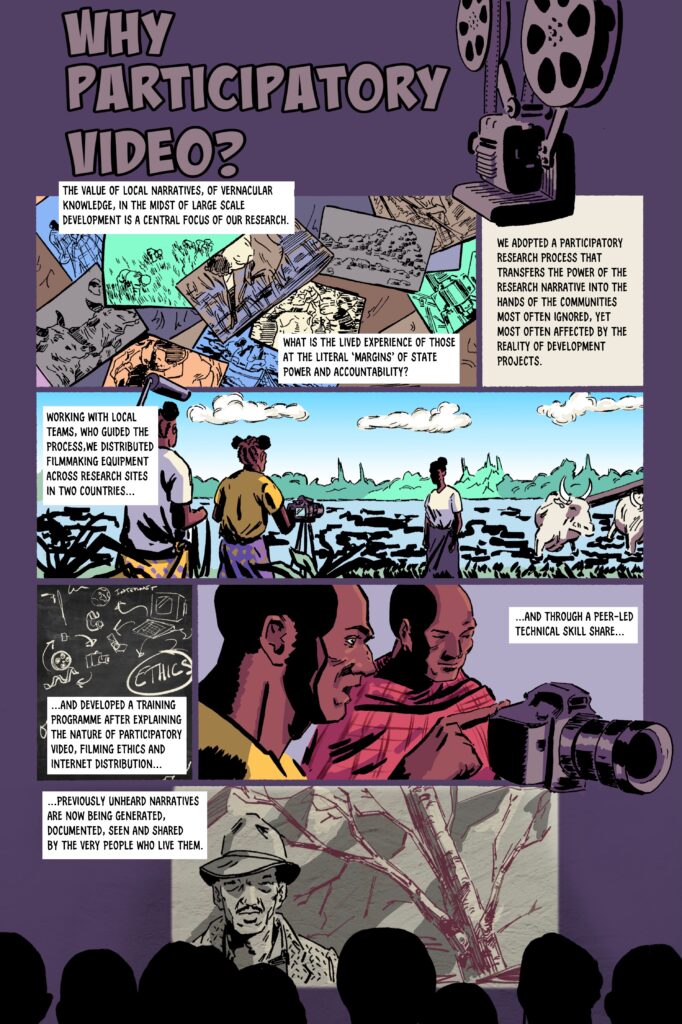

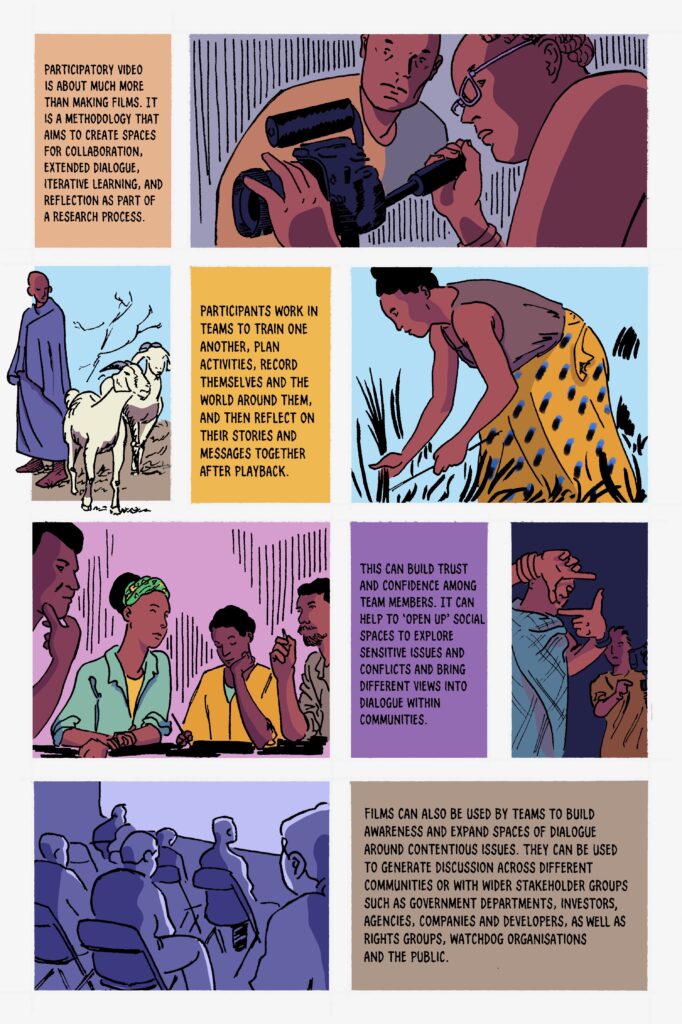

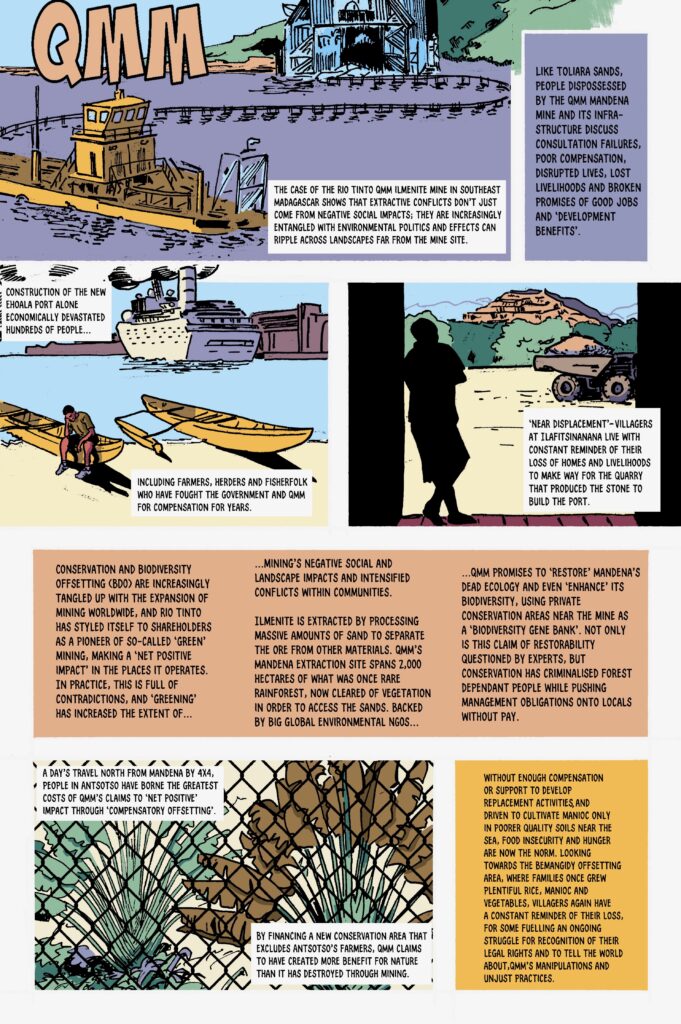

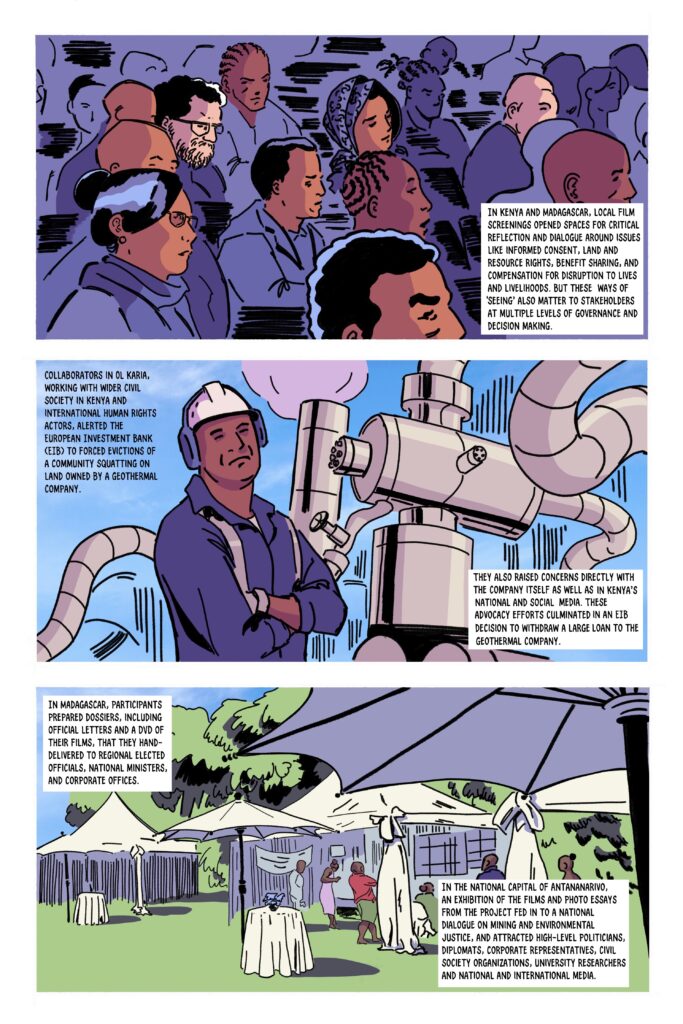

Illustrated by Tim Zocco, this comic explores how this issue has played out in Kenya and Madagascar, as part of the ‘Seeing Conflict at the Margins’ project. The project used mixed methods, including Participatory Video, to reveal the variances among different groups in how they ‘see’ conflict.